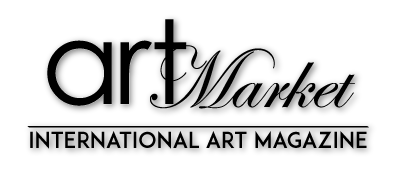

Tony Tetro

An Interview with Genius Art Forger

by Scott Verchin

Tony Tetro in Art Market Magazine. An Interview with Genius Art Forger by Scott Verchin

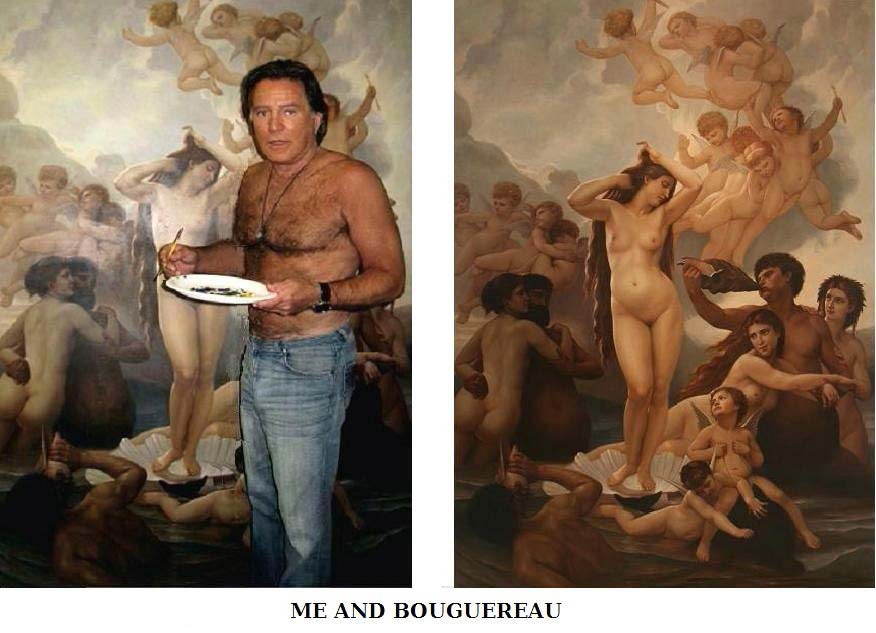

Tony Tetro was the world’s greatest art forger in the 1970’s and 1980’s. In a career spanning over 30 years, Tetro forged works by old and contemporary masters in every genre. From Chagall to Rembrandt to Dali to Rothko, his extraordinary talent was to create works so real, so plausible, that they appeased even the closest scrutiny of the most discerning eyes.

Tetro’s works were regularly passed off as legitimate works in museums, galleries, and auction houses around the world. Los Angeles District Attorney Ira Reiner called Tony, “the single largest forger of art works in America.” In 1989, Tetro was convicted of art forgery in a show trial in Los Angeles. He was released from jail in 1994. Currently he executes master copies for an exclusive list of elite clients from his studio in Southern California.

Scott: Hello Tony, We appreciate the time that you’re giving here for this interview, and in this interview, we would like to focus on your ability and skills to create amazing pieces of work. I see your ability to fake art as impressive.

So let’s talk about how it all started from your perspective, your background and what lead to this road of art forgery?

Tony: I just started to make reproductions when I was married. At the time, I didn’t earn much money as I was selling furniture. So I stayed at home with my wife and my daughter and I just copied things and I was good at it. At that time, I also read a book by Clifford Irving, FAKE! The Story of Elmyr de Hory, the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time (1969). Clifford became famous by writing a fake “autobiography” of Howard Hughes. It was a huge story in the early 1970s and Richard Gere made a movie about him (The Hoax, 2006). Anyway, he wrote a book about fake art, and I was reading it and thought to myself, “I could do this” and that’s how it all started.

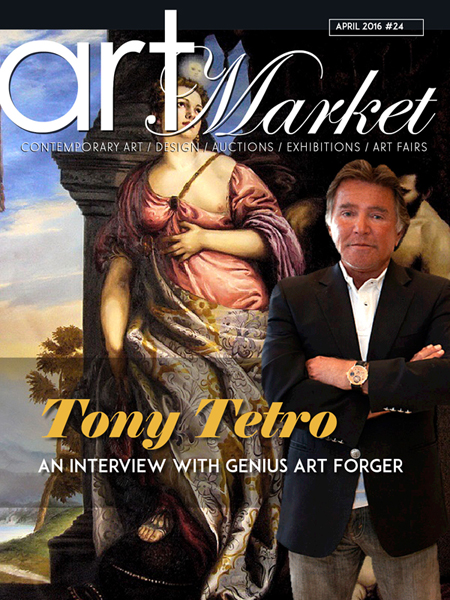

Tony Tetro and Marilyn

An Interview with Genius Art Forger. Art Market Magazine

Scott: Let’s talk about the knowledge of using the right materials. In the beginning as I read, you were making reproductions just for fun. Then it became more serious, more professional. How did you get all the information needed for creating a painting from, say, the Old Masters of the 17th and 18th century?

Tony: Yes. I have to admit I wasn’t very successful at these art fairs, because I put too much time in it. At these art fairs in California, people would look for the paintings where the colors matched their sofa. I would do a Rembrandt or Renoir, and I only earned a few hundred dollars for it. I sold only a few paintings. Maybe twenty I sold.

Scott: Then at some point, you decided to make these reproductions at a high level. Will you describe it? Did it also become an obsession? What was the motivation?

Tony: Well, it was when I read the book [from Clifford Irving] that I knew that I could do this and I felt excited about it and as I started creating fake art. I discovered that I was really good at it. The very first thing I did, that was foolish, was a Modigliani. It was a drawing and it was valuable and it was stupid. I got caught. A man owned an auction house, in Palm Springs, and heard about me through somebody else. I painted for him so, ”he won’t break my hands”. I did a lot of Robert Woods paintings for him. Most people don’t even know who Robert Woods was. In the sixties, and seventies there was no artist that had more prints of his work hanging over sofas in America than Robert Woods. He made seascapes and landscapes. And then he died and nothing. His name disappeared. The silence about his paintings was amazing.

Scott: So at what point did you have this desire to compete and succeed with your art in terms of the value and status of the actual artist? Who did you want to prove this to?

Tony: I started making a lot of lithographs of some other artist whose name I can’t say. I made so many of his lithographs and I sold them to this big art dealer. He sold them to art galleries all over the place and then he found out I did them. He went to all the art dealers and galleries and went out of his way to tell them to watch out of me. Then they contact me and wanted me to work for them. That’s how it really started.

Scott: Let’s go back to the materials and technique. Back then, there was no internet, no YouTube for learning the right techniques, so how did you learn everything? As I read, you were not even formally trained. How do you compare to artists like Eric Hebborn that graduated from the Royal Academy of Art or Han Van Meegeren, that are more classily trained artists. Did you study any of their techniques?

Tony: Yes. Elmyr de Hory. I did and, in fact, I saw his paintings. He was in Los Angeles, I went to galleries, talked to people who knew him. He was here in Los Angeles and sold a lot of paintings to celebrities and he signed them “Hory”. I think he was really good in creating fake art. I was impressed by him. The others…Van Meegeren, for example…if you look at his Vermeers, they were really bad. The perspective was horrible. When you look at Supper at Emmaus, they’re sitting at the table, he copied from a Caravaggio, and the perspective was horrible. The table looked to be a foot wide. I’m not talking about professional jealously here. It’s just that sometimes stories take on a life of their own. DeHory was good. Van Meegeren was overblown, but Eric Hebborn was very good.

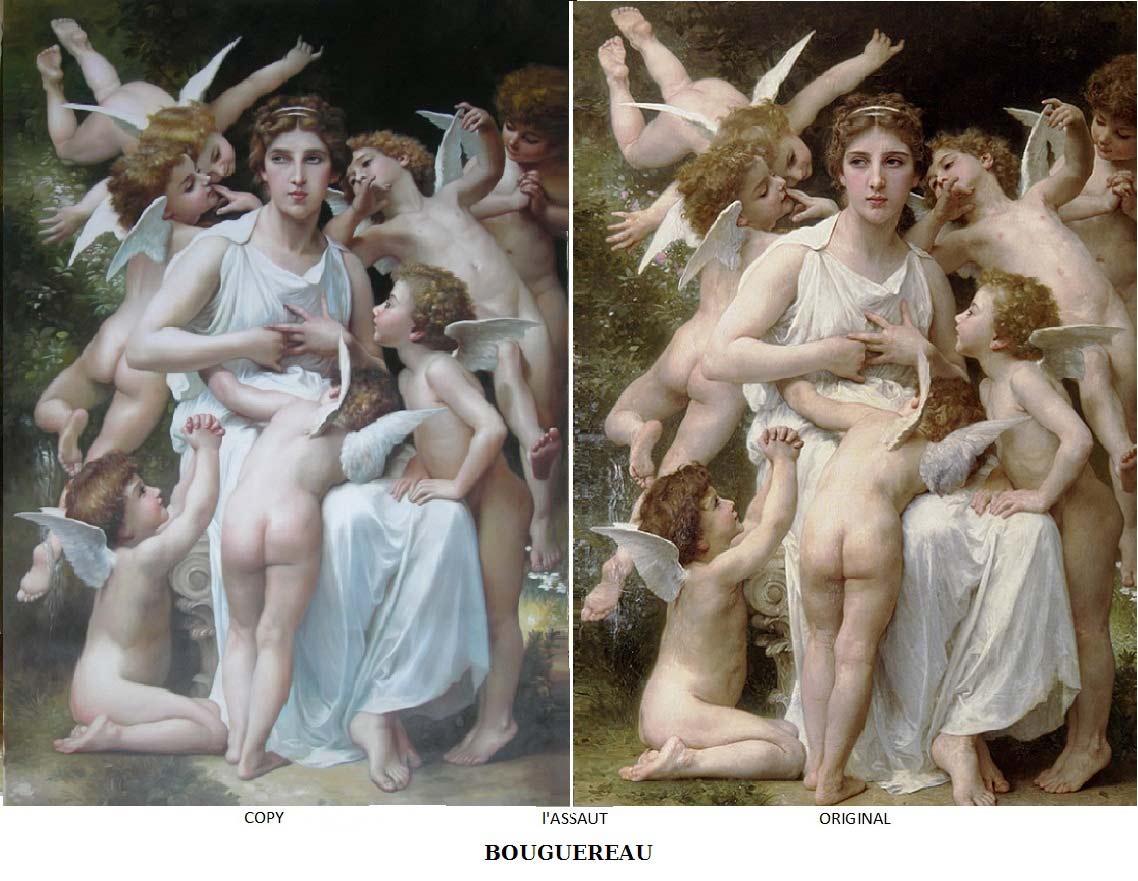

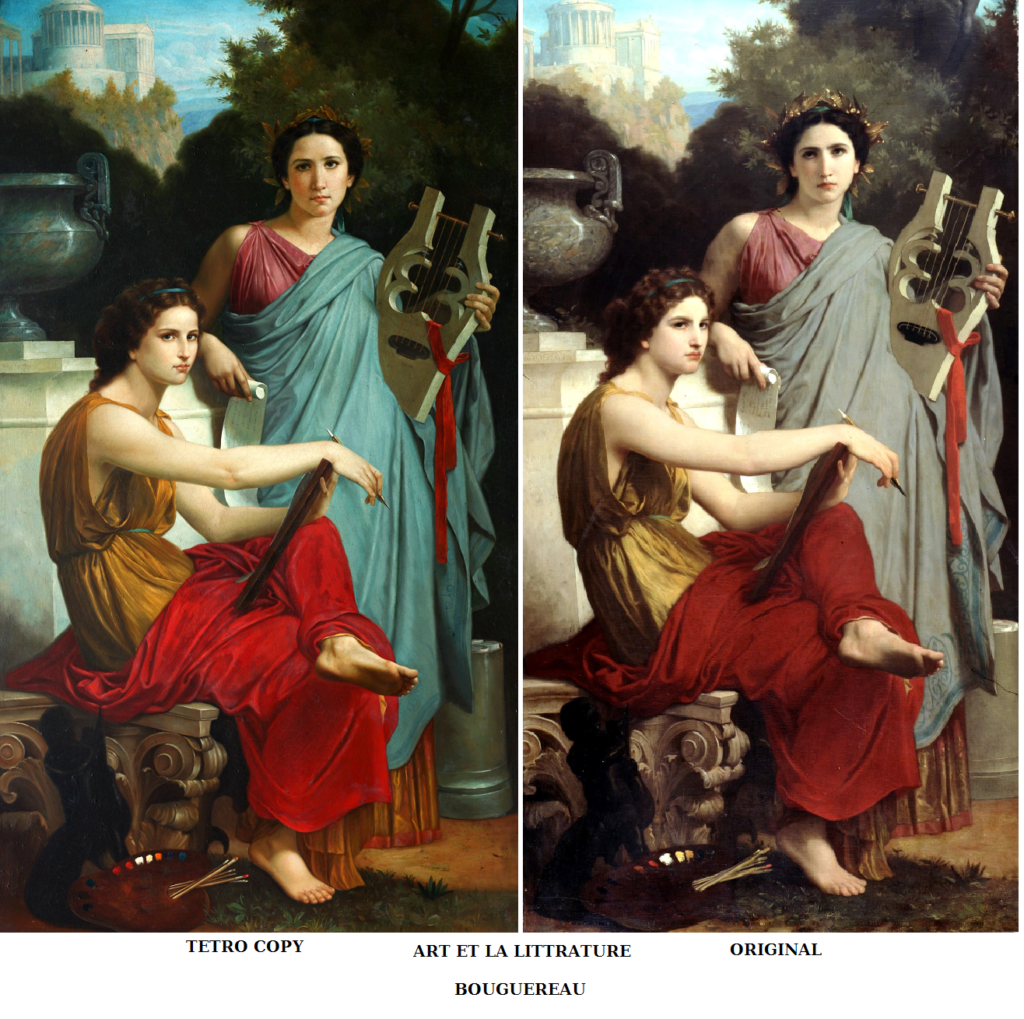

Back in the early seventies, I went to the Uffizi in Florence, Italy and I met an old man named Carlo, who was copying, I believe, a Tintoretto, who taught me to paint flesh like the Old Masters. For four days, I went to see him paint with glazes, a special technique they don’t use in the US. More like Leonardo, Bouguereau and Caravaggio. He showed me how he did it and also taught me how to do flesh very life like.. (The time needed to allow the solvents to evaporate from a freshly painted surface before applying another coat or heat.) It was a big deal to me to learn how to do flesh — and do it right. That was a big step. It helped me paint the Old Masters, which I have been specializing in for the last twenty years. I love Old Masters, but they’re much more difficult, however, I get more money for them.

Old Masters paintings can take a long time and can be incredibly time consuming because these paintings were really big and with lots of details. Some of these paintings could be 7’ x 14’, or larger. I did huge Old Masters. I did one with 50 people in it. So, of course, I used a projector. Like Caravaggio and Vermeer used camera Obscura or other mirror technique, but it’s much easier to use a projector to copy anything. To copy large, detailed paintings without a projector is a foolish waste of time.

Scott: How much time did it take you to learn the style of an artist, the lines and the development in the painting including creating the perfect signature, etc?

Tony: As time passed, I became better, but I got so much work that I hired four people to work in the studio. Each of us had a different palette. We did parts of the painting, each with his own part and it worked out well. We did 95 paintings — big Old Masters for a Texas billionaire. It took five or six years. But now I have a new customer, a friend of his, another billionaire, and that is why I was working today, the whole day.

Scott: How did you get the information about the original materials (pigments/fabric/wood) to discover the techniques of creating the cracks and sfumato (brown color/smoke cover the Old Masters paintings) for the new paintings to look like the Old Masters paintings?

Tony: For the copies that I’m making I’m using Grumbacher Oil. I’m not using the original pigments from the Old Masters as there’s no reason to. I don’t have to now as the paintings are not going to be examined. They come out just as well, however, did you know that the pigments from the Renaissance and the Baroque periods were better than today? I mean, these pigments really glowed, like Rembrandt. When I do the Chagall, for example a gouache, he used Lefranc et Bourgeois gouache and oil paint. The same gouache paint Chagall used. Also Arches and sometimes Japon paper. Japon was one of the most expensive papers in the world at the time. For Dalí and Miró, I bought guarro paper from Spain at times when they used Guarro. There was a period of time in the early eighties, I only did lithographs and etchings. Because everybody wanted Lithographs as they were very popular. I was so busy making these lithographs of Chagall, Miró, Dalí and Picasso that I didn’t paint at all. Then I left the lithographs and went back to painting and made the Old Masters.

Scott: In the BBC series, “Fake or Fortune”, you showed the use of coffee for creating the sfumato. Was that the real technique you used?

Tony: Oh yes, I used the coffee in the pigments as well as the surface. And it worked well! I was doing a Leonardo on that painting to give the paint finish a patina.

Scott: At what point was the moment that you knew you were discovered? When you knew for certain there is no way back and the fake art was discovered? How did it make you feel?

Tony: Well, as I told you before, the dealer that lets everyone know that I was making fakes actually was the tipping point because everyone wanted to work with me. So, back in the day I did contemporary art. I did Miró and, when Miró died, everybody wanted Mirós, and I didn’t have any as I sold them out. So I started with Chagall. Dealers asked me to do Chagall. I did a lot of Chagalls. It’s a sad thing to say, but I learned of Chagall’s death because all the messages on my answer machine were from art dealers trying to contact me requesting Chagall paintings and Lithographs. That’s when I knew I could do very successful in this. In fact, I bought a Rolls Royce the next day. Everybody got mad at me because I doubled my prices. All the art dealers knew each other and they all knew me. They talked about my work and sold my paintings and lithographs and etchings to each other. I made exclusive works for each individual art dealer.

I remember that, at some point, all the art dealers came to LA for an international art fair. That day, I remember they all went to the same restaurant and, as I entered, was immediately shown the best table. All of the people around were talking about me, looking at me and saying to each other “This is Tony Tetro”. That was surprising that people were mentioning my name. Some of them approached me giving me their card, telling me to call them. That’s the day I found out people knew who I was. These art dealers were from all over the world — not just from the United States, but also from Israel.

Scott: Do you feel you achieved the recognition you should have got as a genius of faking art?

Tony: Yes! There was a moment, a big moment, when I knew all of the art dealers already knew of me. Some of them were sure I was from Italy in my 60s. At that time, I was around 33 years old.

Scott: Eric Hebborn used to say that “the fake art should not be less appreciated than the original art, because, until it’s been discovered that it’s fake, it was appreciated and there is no need to less value that art, because it’s beautiful and real in the same way if it’s fake or not. What do you think about this statement by Hebborn?

Tony: It’s true! Many years ago, we made a documentary called “Nova: The Fine Art of Faking It”. They had a German forger. He copied a German artist and when they found out that it’s fake, it became extremely ugly. And I thought, “It was beautiful before, but now, when you found out it’s fake, it became ugly?”

Scott: If you had to choose one artist whose work is most difficult to replicate, who would that be?