Underdogs And The Guardians Of The Door –

An Interview With Eli Petel

by Dr. Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar

Eli Petel is the head of the Fine Arts department at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. He is an acclaimed artist, who extensively exhibited, published and sold both in Israel and internationally.

We met later in the evening; both of us were tired after a long day at work. Sometimes it feels that work is an obstacle to creativity, of the possibility to open and engage. Together, we were trying to explore questions of creativity and life.

Eli Petel .negative-portrait 2002. Negative print

Asaf: Hi Eli. Can you still create while managing a department?

Eli: I create much less than before. I used to work all the time, responding to requests and planning ahead. Now I don’t, I am more passive with my own artwork. There is a lot of pressure, but without the reliefs that accompany regular artistic work.

Asaf: What happens to your soul when your creativity doesn’t get a concrete expression?

Eli: Well, it’s a conflict. On the one hand, I am not creating as many visual works as I used to. But I am no less creative, although the medium has changed. From the more personal, it is now participatory – there is no object, teaching and running an art department is about planning and interacting: I want to plant this seed next to that one.

As an artist you can maintain the same attitude to life – you exercise a relatively solid attitude – it is you in relation to the world, mediated by the object. Now there is no you – it is with others. A whole different story. On the one hand it is not as accurate, not as precise – but on the other, it is much more real.

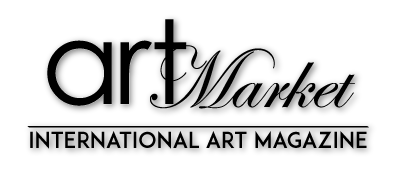

Eli Petel © Artful Dodjer, 2002,oil pastels on paper, 115X141 cm.

Asaf: So when art is expressed in objects it may be more concrete but also less real. Perhaps, then, we can talk about negative portrait. There are artists like Sigalit Landau, who have no problem using themselves as objects, but you bring something much more shy and full of doubt. You let us see the discomfort that comes with presenting yourself as an object. Nonetheless, you’ve chosen to do so.

Eli: When there is an object you can bring your doubt much more clearly: there is a beach, but I actually mean something else… and if you are precise with your object, you can actually convince others. Negative portrait is a culmination of a few ideas, of wanting to change the system; we all know that every photograph has a negative. Yet it can be changed, fooled if you will, by painting, or adding or using other materials. In negative portrait I use make up. My black hair becomes blond, I bleached my black beard – I was changing my own face. What used to be lighter now became shadow; and what used to be shadow – turned to light, using makeup. I developed the negative and then I return to be me. The only place that I haven’t played with was my eyes. I was looking sideways, my eyes were soft.

It was the first exhibition in Israel, which dealt with Sephardi Jewish identity – and it was my choice to use my own face to declare, I am not necessarily what I may seem to be, but I am still threatening, I am still an other. It was influenced by Homi K. Bhabha.

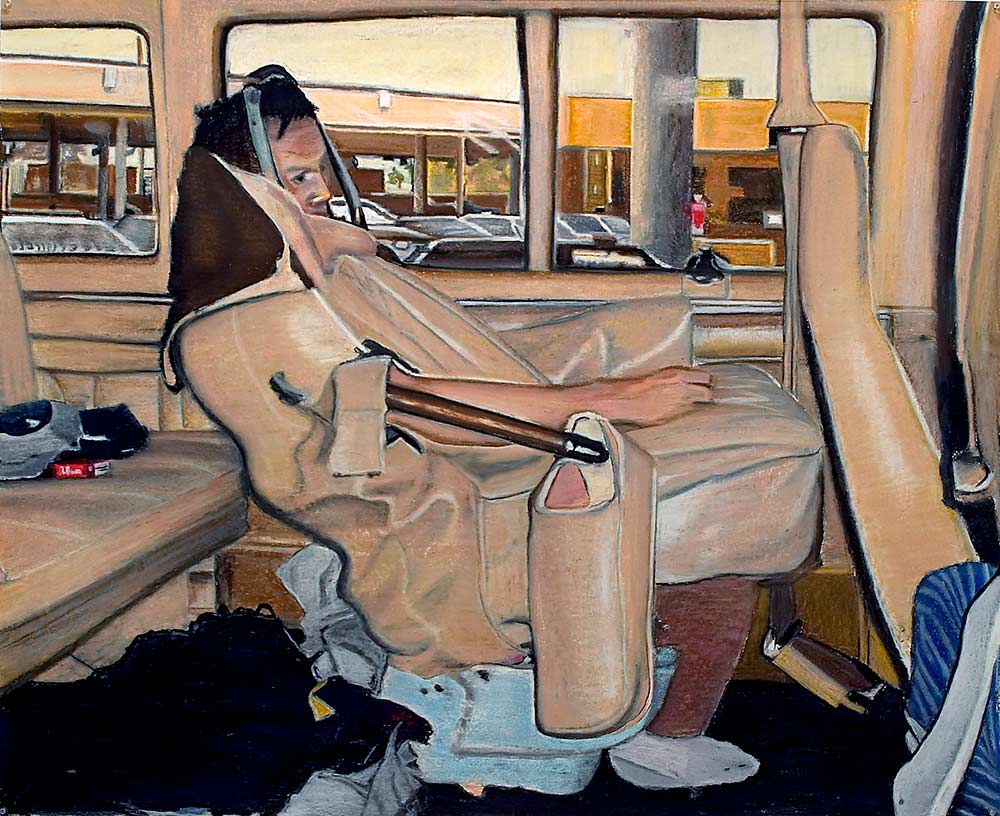

Eli Petel © hyhyh (could this thing be), 2003-2007 beads and fishing line, 160×380 cm

Asaf: It also connects to the palette – the desire to manipulate and change the negative before it goes pear shaped, before it is ruined by organization, there is a wider wish here.

Eli: Yes. You may think that it is about masking, but in my works I tried to expose myself through the uncomfortable pretence, make belief, dressing up – and despite (or because) of these – actually expose and show myself – doing it so seriously that the self-image is full of holes. These holes hold the context: through the lie I attempt to reach the truth, through the make-believe I try to expose the deeper layers.

Asaf: it makes me think of Miley Cyrus. There is a great courage to dialogue through such a medium.

Eli: Actually it connects to punk and hip-hop more than to pop. I can identify through the representations of media these holes and reach out through them. like in hip-hop and punk, I externalize otherness – not trying to justify otherness or justice, but create something embarrassing or alien within the familiar, requiring the observer to go through adaptation and this is where the experience lies.

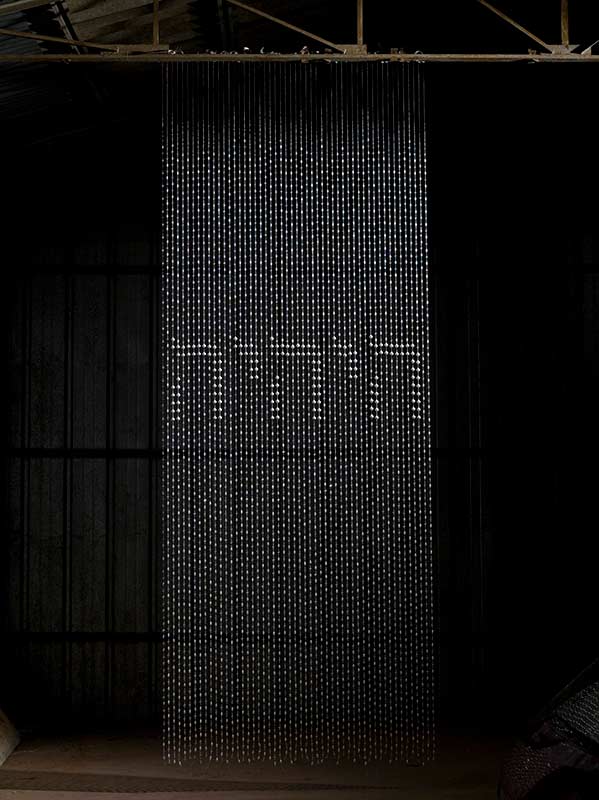

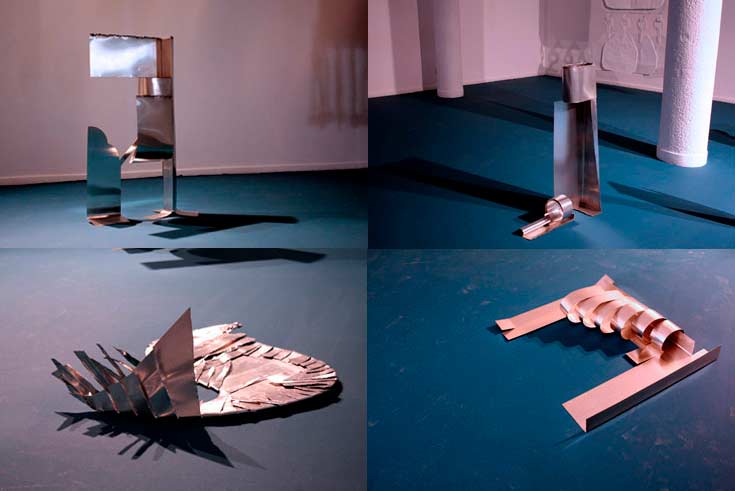

Eli Petel © nine in the dark 2009, installation view, alluminium ,cardboard, verios sizes

Asaf: Like the hummus plate, a play with otherness – alienating and yet belonging to ‘lower cultures’. But what does it mean to be an underdog as a successful painter, and artist, and what it means to be an underdog as a department head of the most important art school in Israel? It probably changes how your previous artwork is seen as well.

Eli: Say more…

Asaf: Even work that you created from an underdog position is, inasmuch as you manage a fine art department, has now become more mainstream. I wonder how do you extract yourself from your work when it receives a new context?

Eli: it is a very meaningful question for me as an artist who takes my audience into account. However, radical I can be in making an image precise, it changes over time and becomes more rounded and organized within a reality. You can see cultural changes in the new interpretations that artwork receives. And I value it as an artist, the work continues to work with time.

Asaf: But what happens when the interpretations of your work move in a different direction to you?

Eli: Well, it’s acceptable. I don’t lock my artwork hermetically. I know certain things about my work that other people don’t know, and they know certain things that I don’t. And the tension and dialogue between these two continues to create a text.

nine in the dark 2009, installation view, alluminium ,cardboard, verios sizes

Asaf: It doesn’t only create a text – it creates you a fresh – because you are reflected in it and people respond to you through it. Let’s take Hyhyhy for example…

Eli: Hyhyhy portrays the awkwardness I feel with Judaism in a form of a gate, a beaded curtain which is a door of kind. The curtain is a buffer, and on the buffer written a word I once encountered but I couldn’t read. Imagine that you couldn’t recognize your own mother, it felt like that – being unable to read something in my mother’s tongue. I researched the word, and understood it was the right zone for me – it was annoying, uncomfortable, it placed an inferior image in a world of progress, and there I actually held back, a cheap eatery.

Asaf: You resist being defined by these social and political agendas on the one hand, but refuse to ignore it and its influence on the other hand.

Eli: Completely.

Asaf: So can we connect it with your work Hila Grocery. It’s so difficult to watch.

Eli: Hila Grocery is a long journey… it has a story. Hila is a friend who showed me an image created by her broken digital camera. And as a painter it seemed as a distortion of the matter, but it was in fact a digital distortion. A violent event created in a visual image, without the mediation of a lens, damaged by digitation. If we compare it to psychology, it’s like an organic neural damage resulting in psychological symptoms.

Asaf: So in that way, it is the opposite of Negative Portrait.

Eli: Exactly. It comes from nowhere and creates a shape which is nothing. I took this image, painted it in a hyper-realistic style and then scanned it with an excellent scanner, and when I printed it – I was showing people a photograph and people thought it was a painting. And the most significant act in this work was the four frames, which I found or stole. These were the only concrete parts. I printed the image into the frames. It was such a twisted act of stopping the world. This image needed to enter the frames, sealing it.

Eli Petel © nine in the dark 2009, installation view, alluminium ,cardboard, verios sizes

Asaf: Hila Grocery makes me feel violent – not towards the painting, but inside of me.

Eli: Yes, as it is a stain. It belongs to the world of phenomena, not the world of wanting and intention – it came from a world between digitation and optics, and it sits there on a fracture, a technological distraction. A photograph which doesn’t need a lens; doesn’t need a reality.

Asaf: You are very socially aware in many of your works, the causal connection – a cause and effect. And here, it is intolerably random. And you frame this random phenomenon without a chance of transcending it.

Eli: I wanted to express something without any reference to politics or even to reality. A philosophical or existential essence.

Asaf: Jar Coffee comes close to it, but it still holds a clear political and social context… but not here.’

Eli: No, Hila Grocery genuinely sits on restlessness. And I am ok with that. My artwork is a process, I spend a long time preparing or thinking about the work. In terms of my reality, people often try to change something with politics – but this is not what I am trying to do. I want to portray the psyche of the politics.

Asaf: Portraying the psyche of politics sounds almost mystical. It makes me think of your work Nine in the Dark?

Eli: It is a mystical work.

Asaf: Any Kabbalistic influences?

Eli: It took me a few years to understand this piece. It is a play, an origami of Hebrew letters. I have chosen letters that I liked and while I worked on this, I had a very frightening dream. In my dream I saw the digit 9 and woke up terrified. For years I tried to understand the dream. And as I worked on my exhibition I was still thinking of the number nine and I tried different combinations of the letters I created, and I got ”Nine in the dark” – which was exactly my dream. I exhibited it at Dvir gallery, the letters which made the words Nine in the dark, alongside three enlarged Americanized talismans. There were Kabbalistic influences, apocalyptic yet nonetheless, I felt there was warmth there and couldn’t understand what it was. And then I realized that throughout it, I was waiting for the birth of my first born child, my daughter… it was the pregnancy.

Asaf: you know, there is so much loneliness there in your work, a loneliness and anxiety which somehow accept itself.

Eli: I am working on something right now connected with Anxiety, perhaps the exhibition don’t touch my anxiety can be a good space for it. Previously, art used to be much more organized, labelled as abstract or expressionism. Today there is much less pigeon holes, there is a greater freedom to be more than one thing, to be positioned alongside a wider and more open definition. There is therefore more space for anxiety, for childishness.

Asaf: speaking of anxiety, can you speak about Artful Dodger? It reminded me of the Chapman brothers.

Eli: It was part of an exhibition of sitting people. One person in a wheelchair; one is interviewed. There is an empty table, where people have left their leftovers. There is a baby in a cradle; I found the photo in the street and wanted to make it famous so the owner might see it and come to collect the photograph. And there is Artful Dodge. It is a painting of a photograph of a real person, a trespasser. The photograph was taken by American police of an illegal infiltrator from Mexico who dressed up as a van seat. He built this seat on his own body, and someone actually sat on him; but immigration police uncovered his costume. It was a real story: a person dressed up as a chair wishing to infiltrate the new world. And Dickens’ Artful Dodger (a pickpocket from Oliver Twist) was a young boy who could sneak in anywhere, illegally reaches any place by breaking norms. The Chapman brothers also deal with what people are willing to do with their body to shift to somewhere else… Artful Dodger is a work of skin, about containing reality, wondering what happened to this sneaking in the internet era, to the desire to be a part of something you’re not allowed in.

Asaf: So how do you view those Artful Dodgers at your doorstep, those aspiring artists, who wish to sneak in, to be a part of the art world and make a living of their art, now that you are the guardian of the threshold?

Eli: I can see myself there, that’s why I remain open. I believe that art offers a real possibility to transcend our cultural and classist background and to demonstrate our capacities and skills beyond those boundaries. Art still holds the possibility of grace, allowing people to get into the door. Perhaps not completely, but art is still beyond class, and so it holds a lot of hope. And I enjoy seeing young people who are hopeful, who are not cynical. Good plastic art is a place for the individual, one of the only places left for a one-man-band, and the dream for creating is beautiful.