AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH ERWIN WURM

By Ida Salamon

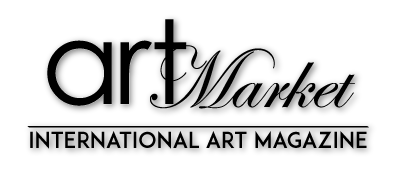

Mixed media. 130x265x480 cm. 2002

Photo credit Arthur Evans

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Erwin Wurm (b. 1954 Bruck an der Mur/Styria, Austria; lives and works in Vienna and Limberg, Austria) came to prominence with his ‘One Minute Sculptures,’ a project that he began in 1996/1997.

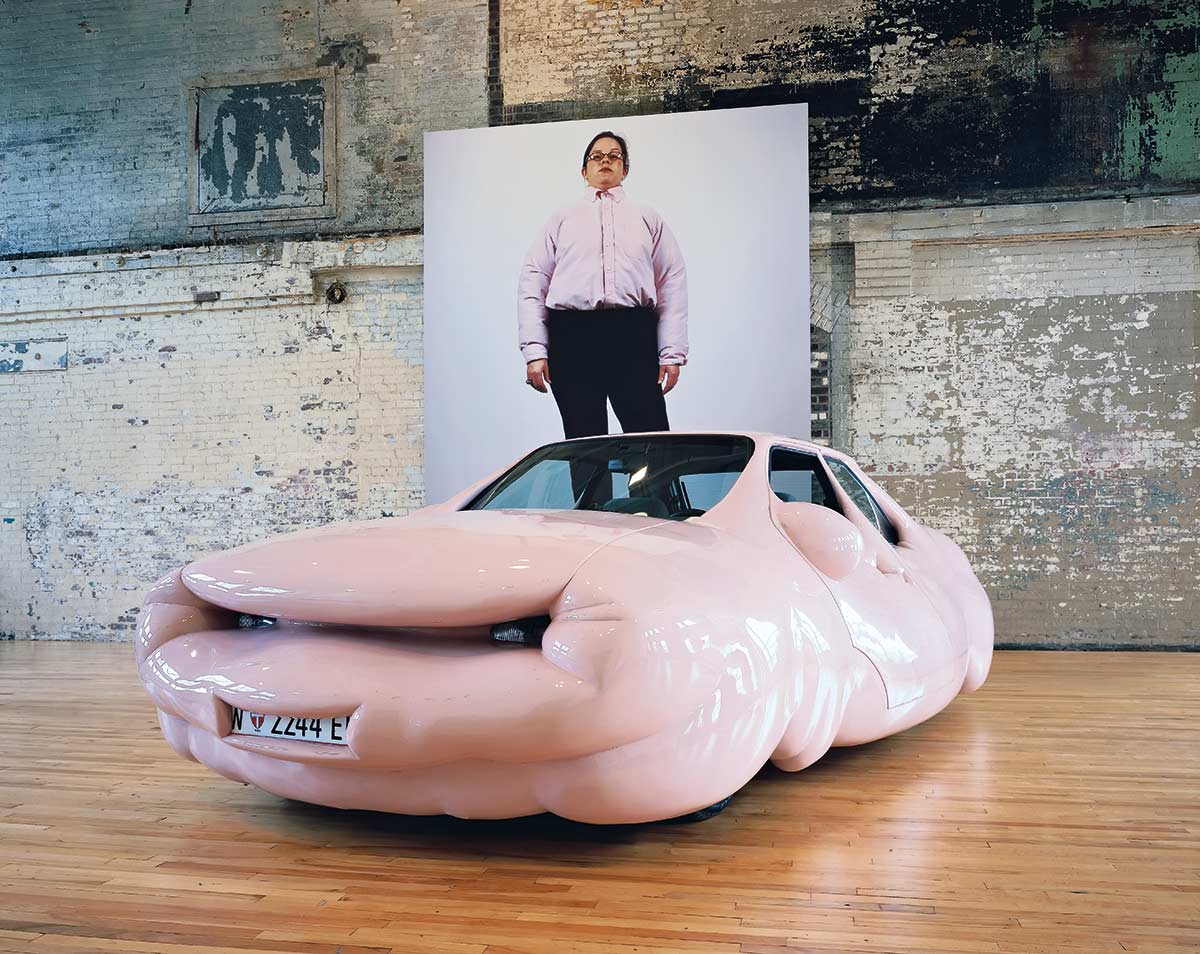

In these works, Wurm gives written or drawn instructions to participants that indicate actions or poses to perform with everyday objects such as chairs, buckets, fruit, or knit sweaters. These sculptures are, by nature, ephemeral. By incorporating photography and performance into the process, Wurm challenges the formal qualities of the medium and the boundaries between performance and daily life and spectator and participant. While in this series he explores the idea of the human body as sculpture, in some of his more recent work, he anthropomorphizes everyday objects in unsettling ways, like contorting sausage-like forms into bronze sculptures in Abstract Sculptures or distorting and bloating the volume and shape of a car into a ‘Fat Car.’

Wurm considers the physical act of gaining and losing weight a sculptural gesture and often creates the illusion of physical body growth or shrinkage in his work. While Wurm considers humor an essential tool in his work, there is always an underlying social critique of contemporary culture, particularly in response to the capitalist influences and resulting societal pressures that the artist sees as contrary to our internal ideals. Wurm emphasizes this dichotomy by working within the liminal space between high and low and merging genres to explore what he views as a farcical and invented reality.

Mixed media. 130 x 469 x 239 cm. 2005

Photo credit Vincent Everharts

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

“Self-determination is something that fascinates me a lot and that I really need. On top of that, we all know that we cannot determine ourselves. We are dependent on our environment, our fellow human beings. The dream of freedom and self-determination is relative.” -Erwin Wurm

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH ERWIN WURM

By Ida Salamon

Ida Salamon: The early days of your career that led to discovering the extent of your talent were not easy for you. Please share with us your memories of these times?

Erwin Wurm: It was depressing and began with tiny miniature sculptures and small drawings. I started drawing as a child, and then at 14 or 15, I couldn’t let it go. This scared my father; he was strictly against it, while my mother supported me instead. My father was a detective, and his dream was that I become a police lawyer and one day maybe a judge or something similar. So it was back and forth, and my God, it was tedious. But, in the end, I persevered and did what I wanted.

Ida Salamon: You applied to the Academy of Fine Arts, but they did not accept you and sent you to the Department of Sculpture.

Erwin Wurm: Everything took place in Salzburg at the Mozarteum. At that time, Salzburg founded an art university. I thought I should go there because I believed that new is always good so I applied for painting there.

But they didn’t accept me; instead, they put me in the Department of Sculpture, and that’s how it all started. After one and half years, I moved to Vienna and came to the Faculty of Applied Arts.

Ida Salamon: It seemed like a huge disappointment for you at the time. How do you see it today?

Erwin Wurm: That was really frustrating, but I told myself, well, it’s a challenge. I accepted that and became interested in the sculpture work. I did not really know what a sculpture actually was at the time. It never excited or attracted me, and then all of it slowly changed. I started to occupy myself with sculptural thinking, which changed my life significantly. Since then, I’ve been doing sculpture, and I’m happy with it.

Ida Salamon: What means the sculpture for you?

Erwin Wurm: In the middle of the 1970s, all I knew of sculptures was that they were “black things with pigeon poops .”I wasn’t interested in them at all. At the time, I didn’t know about Pop Art, sculpture, Dadaism. I had to work that out first because I only looked at pictures until then. So in this respect, I entered a new world that attracted and fascinated me more and more.

mixed media. 540 x 1,000 x 700 cm

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: When you started, you used everyday materials which nobody needed as you didn’t have money for anything else. Please, describe what kind of materials these were?

Erwin Wurm: I had 3000 shillings a month, that’s 210 EUR. I had to go to the supermarket at the end of the month and steal food; otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to survive. I didn’t want to work part-time jobs or at the post office or anything else. I just wanted to make art, so my work shouldn’t cost anything. I was able to take carpentry waste, then I changed my studio, and there were old cans or junkyards, and I worked with them. After that came clothing, so I developed my art to incorporate fabrics. Not only were the materials from my immediate surroundings, but the content was from my immediate surroundings as well.

I discovered that everything that exists in this world has the potential and can be used to make works of art. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a car, a table, or a pen. At some point, I realized that my topic is our world and time, always expressed visually in terms of sculptural language. I’ve been doing that for the past forty years.

Ida Salamon: Which materials do you use today?

Erwin Wurm: Different materials such as polyester or concrete.

First, I have an idea, then I think about the concept, whether the medium better lends itself to a photo, a sculpture, or a performance. That helps me decide which material I will use.

Ida Salamon: You are a world-renowned Austrian artist with a recognizable signature, and your works command high prices. You work “with passion and love and only what you want,” as you said. Apart from the fact that it enables you to live a comfortable and almost self-determined life, what meaning does it have for you?

Erwin Wurm: Self determination is something that fascinates me a lot and that I really need. On top of that, we all know that we cannot determine ourselves. We are dependent on our environment, our fellow human beings. The dream of freedom and self-determination is relative. I used to take orders, but I can’t do that; it exhausts me extremely.

There is a level of expectation, and in the end, I don’t have a free decision but am committed to fulfilling what the others demand. That is the whole dilemma that architects have to deal with constantly, this discrepancy between the free design and the construction.

I always wanted to avoid that, so I prefer not to do any assignments. And that’s a good thing. I am fortunate that I don’t have to worry about paying my rent. It happened at some point, and I am very grateful for that. I never dreamed that I would earn more and have more and more success. That was, of course, a surprise, and I wouldn’t realize it for a long time.

(Concrete Sculptures). 2022

concrete, tire. 85 x 45 x 60 cm

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: Was your work accepted from the very beginning?

Erwin Wurm: Here in Austria, people are often pulled down and envy each other. I don’t know where this energy comes from; it’s crazy. Nevertheless, I was lucky, and I have to say that during my development as an artist, I received support from a few people who thought my work was promising, but a lot of rejection from people who were trying to damage my career, not taking me seriously. That hurt me. I often think of young people and how they are put down. That bothered and stressed me, too. But that’s the way it is, and many people are struggling with the issue. At some point, it is no longer relevant, and I didn’t give a damn. You have to go your own way, and it works. My success abroad started earlier, first France, then America and Asia.

Ida Salamon: You ask socially relevant questions with your art; you are strong against defamation which you, yourself, experienced at a young age, show petit-bourgeois symbols. Which statement do you give with your art?

Erwin Wurm: The sculptures speak for a particular time about the kind of world and society I come from, where I grew up and in which I developed. Everything together results in a horizon, and I try to let it flow into my work.

Then, finally, comes a personal story with my family. That doesn’t mean that I tell the stories about my grandmother, who cares about lunches with my grandma. But I want to give these experiences a generally reasonable level because I think it has a justification. It is interesting how the post-war society treated its young people;

we were beaten at school.

The old Nazis were part of the government. My “Narrow House” is actually my parents’ house. When you enter inside, you get a claustrophobic feeling. All the houses of that era were similar, with similar furniture and details. Everything seemed so narrow that you felt cramped. This is my statement for the time in which we lived. That was a restrictive society, but today’s society is also restrictive in other ways.

concrete, wood. 28 x 37 x 56 cm

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: You also set up the “Narrow House” in Venice near the Palazzo Cavalli. What kind of experiences did you bring from there?

Erwin Wurm: The “Narrow House” was presented next to the beautiful Palazzo, this small Austrian family home with constrained architecture. My heart bled, and I thought, my God, how did I get here. These are entirely different worlds, how people lived there and how Austrians lived. I have always felt that the environment, the architecture, what we see, what we speak, what we surround ourselves with strongly influences us and our thinking. So I would say that it almost hurts when you see this cultural clash.

Mixed media. 7 x 1,3 x 16 m. Installation view. Superstress. La Biennale di Venezia, Palazzo Cavalli Franchetti, Venice, Italy, 2011

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Mixed media. 7 x 1,3 x 16 m

Installation view. Superstress. La Biennale di Venezia, Palazzo Cavalli Franchetti, Venice, Italy, 2011

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: With “One Minute Sculptures,” you have invented something new; you also give the work of art its name, it is one minute or less in length and is captured in a photo or drawing. This form inspired ‘Red Hot Chili Peppers’ in an MTV music spot. How did you arrive at this idea?

Erwin Wurm: I’m always interested in forms of our society and our time. We live in a time where everything is disposable.

I wanted to create a fine sculptural form that is also short-lived. I experimented, and my first objects lasted only the exhibition’s duration. At some point, I came up with the idea to make these short-lived sculptures that exist for a minute or two or even a few seconds but then disappear. I had to take pictures or drawings of them to capture them. That’s how they developed.

(One Minute Sculptures). 2014

Pedestal, utensils, instruction drawing

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: Two years ago, at the start of the global pandemic, you provided the baroque altar of St. Stephen’s Cathedral with a huge violet knit sweater. The oversized hot water bottle on human feet, “Big Mother,” was set up in the entrance area of the cathedral. Viennese people could admire your art during the first lockdown. How did you spend those two years since then?

Erwin Wurm: Those were not good times because our freedom had been curtailed quite drastically. Although I understand the need to protect others, particularly the weak ones. Many have died; you couldn’t freely hug each other. Consequently, it was really not a nice time. On the other hand, I have to say it wasn’t that bad for me because I was in a privileged situation. We live in the countryside; we grew our own vegetables, harvested radishes and tomatoes.

I could concentrate on my work more because we were not allowed to travel. On some level, it was actually relaxing and pleasant. Unfortunately, I had to let some of the employees go.

Ida Salamon: Don’t you miss the big cities? You have lived in New York and Vienna.

Erwin Wurm: Of course, after a while, I began to miss it. I wanted to go somewhere else and to see something different. I was accustomed to traveling a lot for my exhibitions. However, I became fearful of the pandemic. But I still live partly in Vienna, my wife and my daughter who goes to school are there. That is my life now—between different places.

Ida Salamon: You criticize obesity and consumption with your sculptures. You put humor and cynicism in them. What did you want to show with Cucumbers Self-Portrait?

Erwin Wurm: The absurd also interests me; I would like to mention that. Humor is part of the absurdity of the paradox. Regarding the cucumbers, it is a separate story. This again has to do with my family and my childhood years.

My grandfather always rewarded me with pickles after

a walk. Just like sausage, that’s a lower-middle-class cultural asset. That was also an important food for me as a student. And at the same time, the cucumber and sausages refer to a male body part related to the drama our world is involved in. The toxic masculinity that breeds the wars and oppression, which kills people, is connected to this organ. It’s inseparable, and I like to make fun of it.

I bring this up for discussion and show it in another configuration. And I made a self-portrait with it because many men think about their cock; pardon me for putting it that way, they have a cock in their head instead of their brains. What does that mean when I present myself with so many cucumbers? That’s intended cynically; that’s meant to be funny. But can it be something else? That’s a question I’ll pass on.

Mixed media 2017. Performed by the public.

Austrian Pavilion, 57th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2017

Photo credit Eva Würdinger

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: “I am a political person” and “there is no such thing as justice,” you once said. What is the state of the world today?

Erwin Wurm: Our world is not in a good state; there is no need to explain that. You just look at climate change, the water getting worse and worse, the piles of garbage growing, the animals being treated terribly.

Everything is being industrialized, exploited, and put down; that’s frightening. But what’s also scary is how people treat one another. Human beings are destructive; it is difficult to grasp. Mankind is in denial about how they come to destroy everything. It’s getting worse and worse. For example, the pandemic and this aggression by the right-wing extremists are insane and frightening.

Ida Salamon: You radiate calm and balance, and you seem to be someone who can’t stand chaos. Is that your nature, or are you working on it? How do you cope with life?

Erwin Wurm: That’s right, I can’t stand chaos. I’m balanced at work, personally not. I’m always torn, and I always wonder about the state of my work. I have never been satisfied with what I have achieved. I think that would be fatal and a mistake; you have to prove yourself over and over again. This keeps me going. It’s always exciting and challenging; it’s always full of joy but also full of fears. And I love it.

I have a fitness trainer who comes in three times a week, I have my shiatsu, I read a lot, and I spend time with my family and friends who are my extended family.

Ida Salamon: “Art enables us to see things differently, also because nature, art, and culture fascinate us endlessly,” you said. What do you find fulfilling?

Erwin Wurm: Love, family, friends. What drives me makes fascination and beauty possible: The architecture, the literature, not just the pictures; it is music and philosophy. The spiritual achievements of people fascinate me. Sports are necessary but not nearly as exciting as visiting a museum or a good book. Everything that goes on in my head.

“The “Narrow House” was presented next to the beautiful Palazzo, this small Austrian family home with constrained architecture. My heart bled, and I thought, my God, how did I get here?” -Erwin Wurm

Mixed media. 7 x 1,3 x 16 m. 2010. Installation view

Sculpture at Pilane 2015 , Klövedal, Sweden, 2015

Courtesy Sculpture at Pilane 2015

Erwin Wurm © All rights reserved.

Ida Salamon: You were teaching for a few years; what did you pass on to your students? “Talent alone is not enough; the artist needs a lot of luck and diligence to become good,” you said.

Erwin Wurm: I had a good relationship with students. I’ve had a reputation for being strict but fair. I took it seriously; I was always present and had personal meetings, we discussed everything. I have tried to answer questions because I can remember that I often did not get answers to the questions I asked as a student. I tried to do it better, but I don’t know if I succeeded.

“Love, family, friends. What drives me makes fascination and beauty possible: The architecture, the literature, not just the pictures; it is music and philosophy. The spiritual achievements of people fascinate me.” -Erwin Wurm

Ida Salamon: Your works can currently be seen at the Museum Albertina Modern in Vienna, in the exhibition “Schiele and his Legacy.” The picture with four bananas stands directly opposite Schiele’s nude self-portrait. What did you want to tell the viewer with this photo?

Erwin Wurm: The banana is similar to the cucumber. I was voted as Artist of the Year in Germany in 2007. I just wanted to play silly, not taking it seriously and making fun of this election.

Ida Salamon: Where can we see you next? What are your plans?

Erwin Wurm: There are several projects I’m working on: in Berlin, Paris, Belgrade. There are many sculptures to be further developed. I am very excited and looking forward to the vast exhibition of large and small objects, photos, and pictures in the Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade. It will be completed with a catalog.