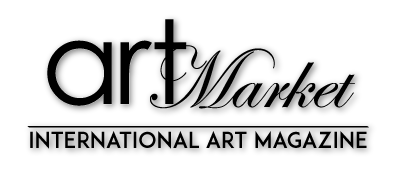

Hilma af Klint – Paintings for the Future

Exhibition Coverage by Scott Verchin

Hilma af Klint – Paintings for the Future Exhibition Coverage by Scott Verchin. Photo: Scott Verchin for Art Market Magazine © All Rights Reserved

When you think about the pioneers of abstract art, the names that come to mind might include Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich. It’s a safe bet that Hilma af Klint does not enter the conversation. In fact, many people are not even aware of her career overall. As an art history student at Syracuse University in the 1980s, af Klint was not part of the curriculum – and for good reason – as she was virtually non-existent to the art world at large. Her abstract paintings actually predate these aforementioned names, as she remains, in many circles, one of modern and contemporary art’s best-kept secrets.

Hilma af Klint, Exhibition View. Photography by Scott Verchin. Art Market Magazine © All Rights Reserved.

Hilma af Klint was born outside of Stockholm in 1862. As the fourth child of a Swedish naval commander, af Klint spent summers in Lake Mälaren where she had her initial contacts with nature. It would be these associations with natural forms that initially inspired the early stages of her career as a more traditional painter of landscapes and portraits. From 1882-1887, af Klint studied at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm where she mastered classical techniques and concepts – including Impressionism. Her loose brush strokes and usage of light were becoming evident during this time.

In 1896, Hilma af Klint and four other women formed a group called “De Fem” (The Five). Together, they made contact with so-called “Höga Mästare” (The High Masters) from another dimension via séances. At this point, art and spirituality remained two mutually exclusive components of her life (she rarely exhibited her works then) but that was about to change. She developed a form of automatic drawing, which involves unconscious writing without guiding the movement of the pen on the paper. Simultaneously, af Klint progressively detached from her past academic training.

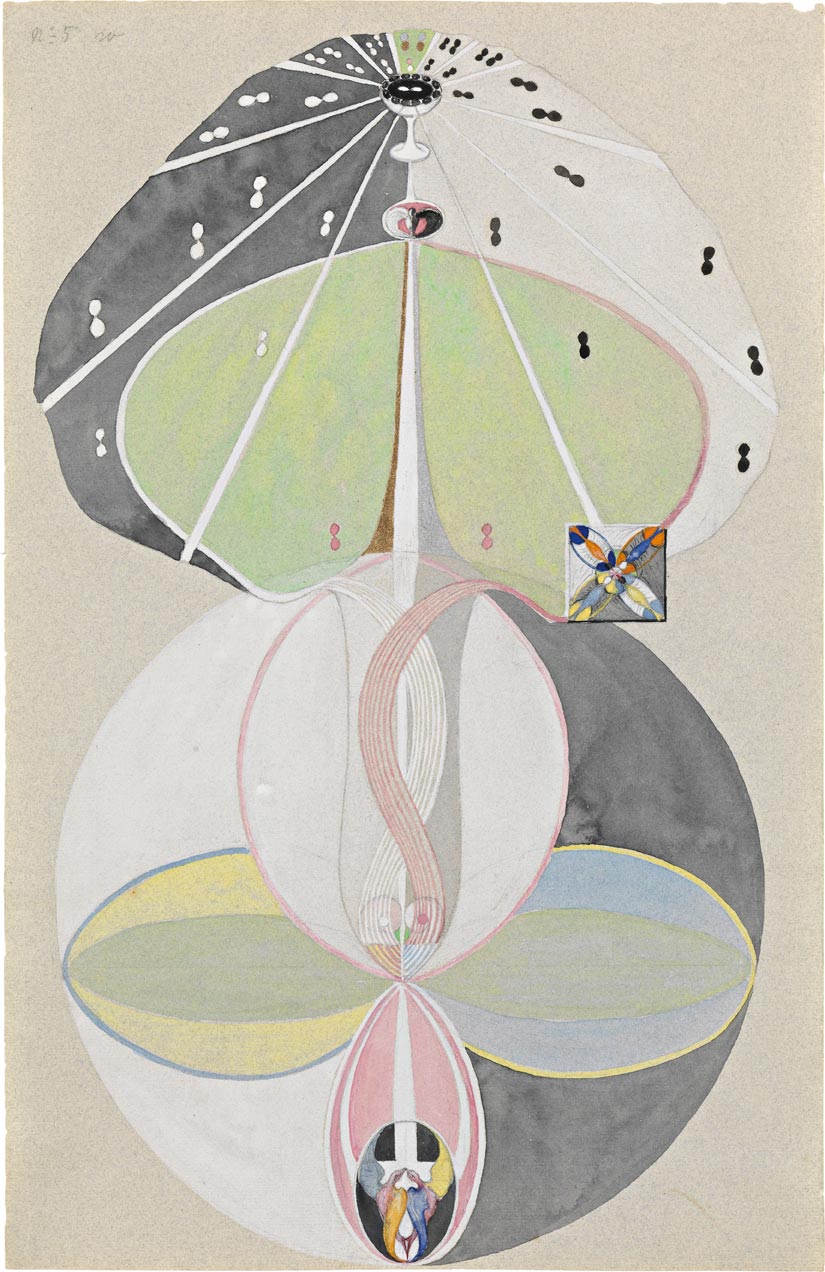

Shortly thereafter, by the mid-1910s, af Klint began focusing more on her abstract style as she became more involved in spiritualism. She claimed to have been commanded by The High Masters to create what was to become The Paintings for the Temple, which was the tipping point in her career as af Klint pivoted from figuration and gravitated towards more spiritual subject matters. These 193 paintings and works on paper (1906-1915) completed her transformation into the abstract world that would ultimately define her as an artist.

Hilma af Klint, Exhibition View. Photography by Scott Verchin. Art Market Magazine © All Rights Reserved.

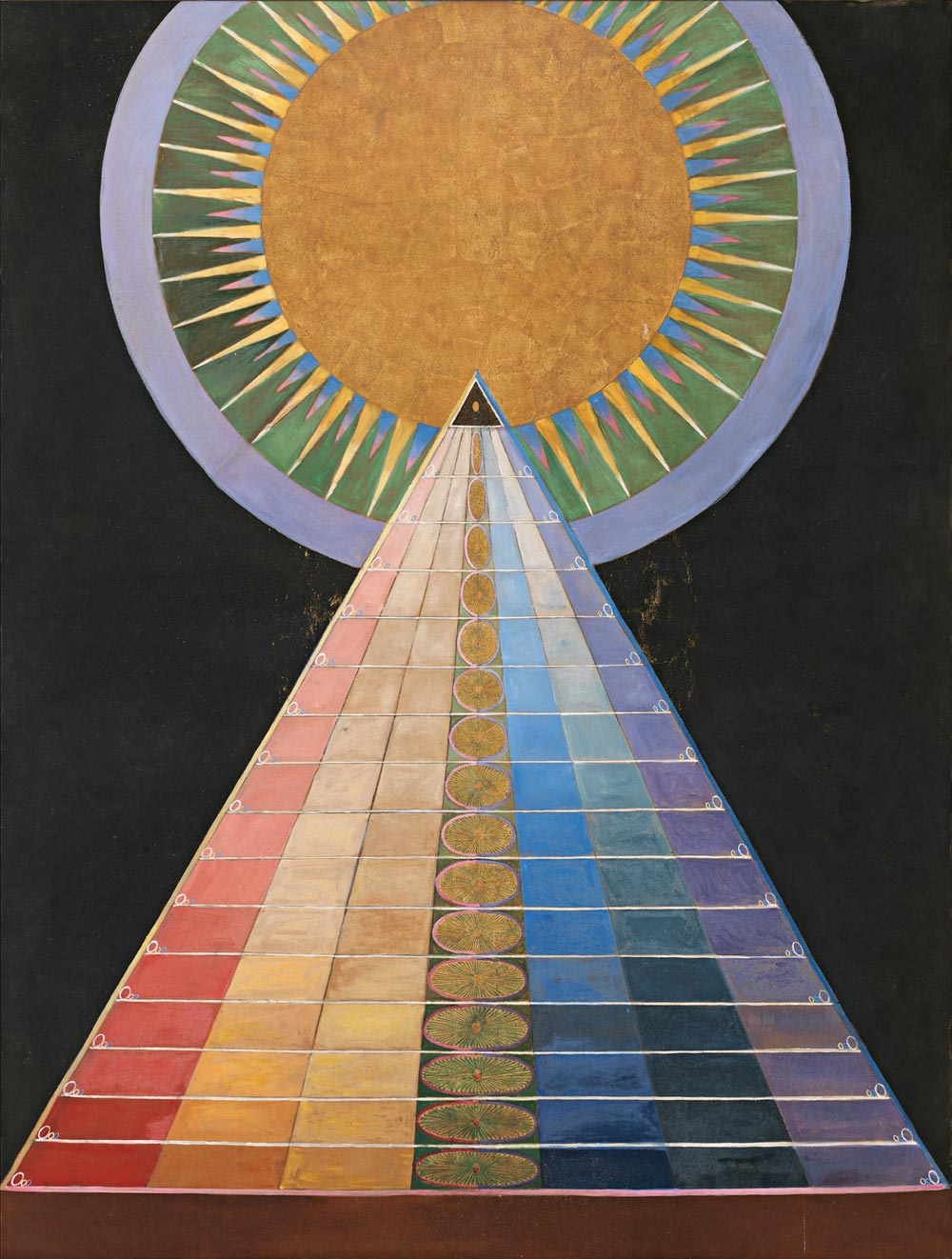

“Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York serves as the ideal venue for this comprehensive retrospective as the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed cylindrical building was conceived as a “temple of the spirit”. In 1915, af Klint imagined installing her compositions in a multilevel temple connected by a spiraling path, which, coincidentally, resembles the design of the Fifth Avenue museum.

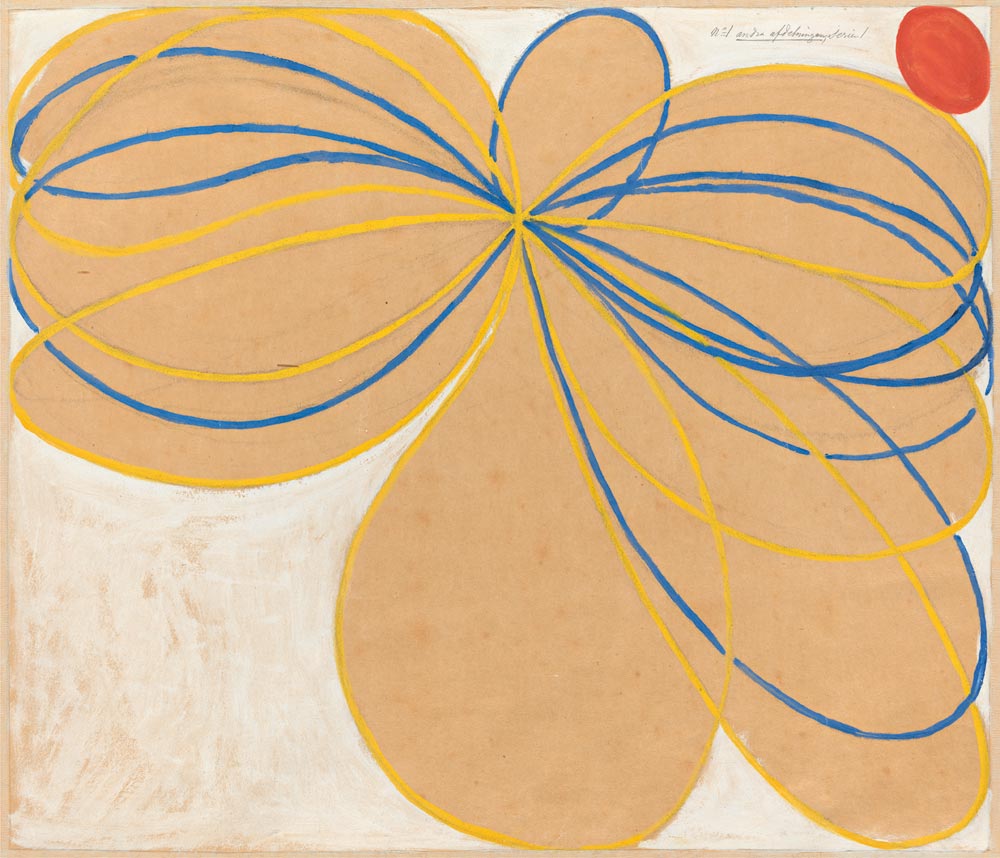

The exhibition creates an almost immediate impact at the ground level when visitors are introduced to The Ten Largest, a series of larger-than-life bold, colorful abstract paintings, which are untethered from any recognizable references to the physical world. These floor-to-ceiling masterpieces represent the cycle of life: childhood, youth, maturity and old age. Furthermore, the femininity of these works, from a contemporary perspective, is clearly on display by virtue of form, shape and color that run rampant throughout each of the paintings. Blossoms, lacy garlands as well as various cursive lines along with an abundance of pink, lavender and peach palettes reaffirm the feminist symbolism and iconography throughout. These paintings are unmistakably powerful and spellbinding. While, aesthetically, each of these canvases may seem to possess its own identity, they are destined to be displayed collectively in order for us to properly connect with them. Whether you accept or reject occult practices is irrelevant, we must follow the chronological progression of these works to parallel the cycle of life so we gain a greater understanding of af Klint’s vision of The Ten Largest as a beautiful wall covering in a temple.

Hilma af Klint, Exhibition View. Photography by Scott Verchin. Art Market Magazine © All Rights Reserved.

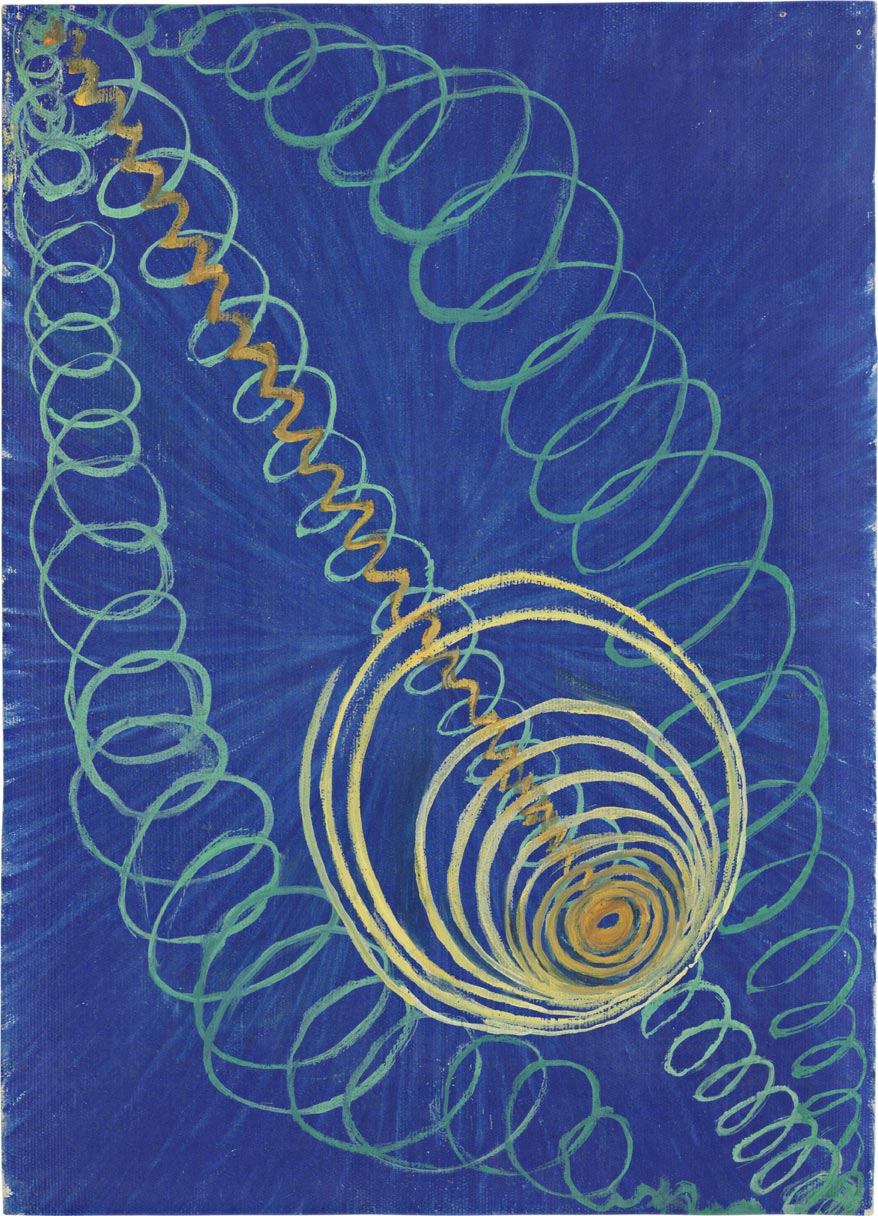

Despite the grandeur and energy of these monumental paintings, we continue to spiral upwards (a spiritual metaphor) and further examine the visualization of af Klint’s abstract world. Her first group of works, Primordial Chaos, symbolizes the origins (or birth) of the world. This series of 26 small-scale oil paintings, predominantly blue, green and gold, represent water, earth and light, respectively. The figures and forms of these paintings are connected to af Klint’s scientific background – specifically, cosmology – and are derived from her time spent as a biological illustrator.

Hilma af Klint, Exhibition View. Photography by Scott Verchin. Art Market Magazine © All Rights Reserved.

The Paintings for the Temple was segmented into focused groups as they collectively depict an evolutionary tale. Each composition was created and curated to have a purposeful relationship with its neighbor. In Evolution, the spiral plays a critical role in epitomizing continual growth and change.

The same can be said for The Swan as af Klint focuses on dual forces such as life versus death and black versus white. The swans initially conflict with each other, and then combine before becoming completely unified as one.

The Paintings for the Temple culminates with three large Altarpieces, which, at first glance, remind you of an Egyptian temple with its pyramid, rainbow and sun symbolism. Once again, af Klint deploys dualities here as one of the equilateral triangles points upward towards to the heavens and the other points downward. The center composition contains a circle with a thick black outline, like a protected membrane, with a small six-pointed star buried deep inside its core.

Remarkably, this groundbreaking artist showed examples of her abstract work perhaps only once during her lifetime, and she stipulated that The Paintings for the Temple should not be seen until twenty years after her death. “I think her impulse not to show the work to the public, and to hold it pretty privately throughout most of her life, was really motivated by wanting an understanding audience,” says Bashkoff. In the 1980s, some years after af Klint’s prohibition had reached its end date, her paintings were shown in a few exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. For the artists who saw those shows, af Klint’s artwork came as a revelation. Artist R.H. Quaytman was among those who both saw and exhibited af Klint’s work; paintings by Quaytman that engage with af Klint’s practice are on view on the Guggenheim’s top ramp. In the Hilma af Klint catalogue, Quaytman notes of af Klint’s work, “If you . . . didn’t know anything, you’d think these paintings were made ten or twenty years ago. You would not know how old they were. And what’s so thrilling about her work, I find, is how contemporary it feels.”

While Hilma af Klint remained a practicing Lutheran for most of her years, she was deeply interested in a variety of religions and spiritual teachings from a very young age. Whether it was Hinduism, Buddhism or other esoteric belief systems, religion and spirituality played a dominant role in her life, which was reflected in her artistic career. The significance of color, form, line and the juxtaposition of objects can be seen throughout her works.

Hilma af Klint died in 1944, aged 82, due to complications she suffered from a traffic accident north of Stockholm. Her will mandated that her paintings not be shown for, at least, 20 years after her death. That said, it wasn’t until the 1960s that the world first became exposed to these revolutionary masterpieces. It would be another two decades before her works would finally be shown at a Nordic conference in Helsinki in 1984. Her 1,200-piece collection is currently owned and managed by the Hilma af Klint Foundation in Stockholm.

“HILMA AF KLINT: PAINTINGS FOR THE FUTURE”

is on exhibit at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York NY USA, through 23 April, 2019.

Read the full article on Art Market Magazine Issue #42