AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH

JACOB AUE SOBOL | MAGNUM PHOTOS |

BY JOSÉ JEULAND

Originally published in the International Lens Magazine for Fine Art Photography

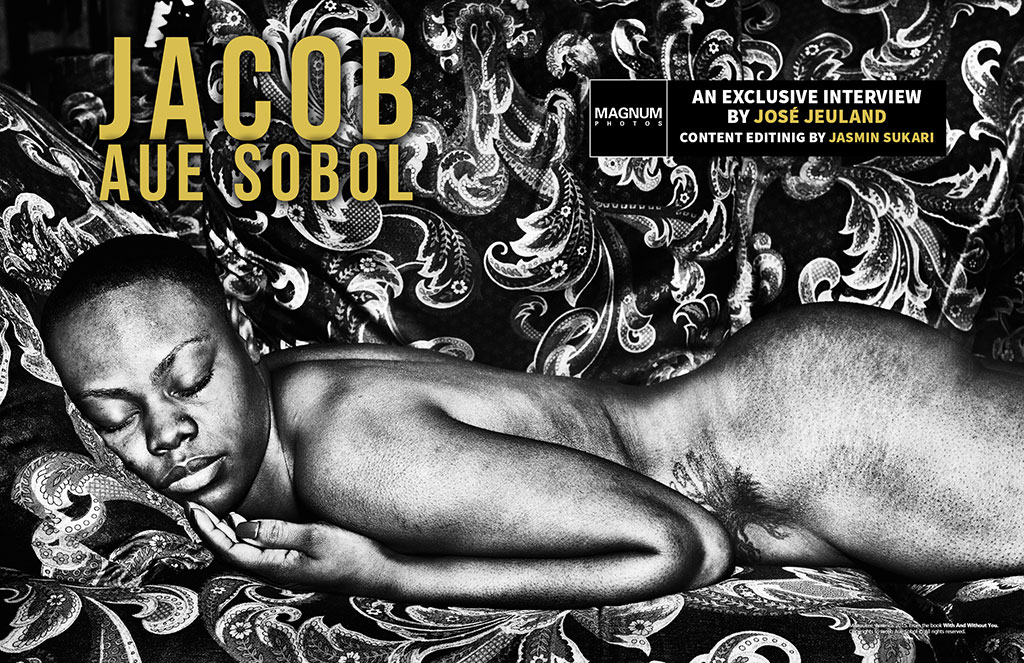

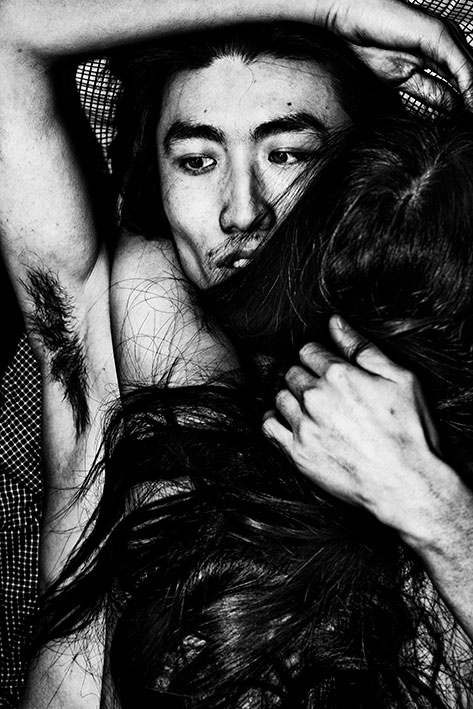

Jacob Aue Sobol is known for his expressive style of black-and-white photography.

“My pictures are about being human for better or worse,” he says. “I cannot imagine dealing with other themes. It is the core of my pictures that they ask questions about our existence and that they speak to our inner feelings.”

Sobol’s Greenland, Guatemala and Tokyo photographs had won him numerous awards.

In 2006, Sobol moved to Tokyo and shot a series of images that won the 2008 Leica European Publishers Award. His series, “I, Tokyo,” was published by Actes Sud (France), Apeiron (Greece), Dewi Lewis Publishing (Great Britain), Edition Braus (Germany), Lunwerg Editores (Spain), and Peliti Associati (Italy). Sobol became a nominee at Magnum Photos in 2007 and has

been a full member since 2012. Following his time in Tokyo, Jacob worked extensively in Bangkok, resulting in his 2016 book, “By the River of Kings.” granted by The Danish Arts Foundation in 2016 and The Danish Arts Council.

Sobol had also worked in Denmark, Thailand, The United States of America, Russia, and China; his latest book, “With And Without You”, collects a selection of images made over his 20-year career to date.

On his website, “With And Without You” is described as a tribute to his father.

Since then, He has been working on some ongoing projects in Denmark (“Home”) and in the United States (“America”). Since then, He has been working on some ongoing projects in Denmark (“Home”) and the in United States (“America”).

“My pictures are about being human for better or worse.”

– Jacob Aue Sobol

It is a great pleasure to publish an exclusive interview with one of the most impressive, unique fine art photographers and dive into his inner world, a private world of extraordinary creativity in extreme Black and White.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: Hello, Jacob, and thank you for this interview. Let’s start from the beginning. Your education in photography began at the Danish European Film College and later on at Fatamorgana for Art Photography in Copenhagen. Would you say the studies of film photography influence your current style?

Jacob Aue Sobol: When I was at school at Fatamorgana, each week, we had a new guest teacher, and I would try different things. I was almost a complete beginner, and my pictures would change basically every week. Only when I finished school and moved to Greenland I was challenged to find myself and my own language. I basically arrived there as a documentary photographer or a traditional photojournalist – using a big camera, looking for dramatic moments, finding classically intense compositions, etc.

But then, when I was with my girlfriend at the time, Sabine, I started photographing using my pocket camera as a way to preserve moments with her and pieces of my life there that I felt close to, and I arrived at a way of working that was much more free and spontaneous. If there has been a common thread in my photographs since then, this same search for love and a human connection compelled me to start retaking pictures in Greenland.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: Your work is very emotional. It can be described as rough and deep, trying to express intimate moments of humanity. How did you develop, or should we say, enhance your style over the years?

J.A.S.: Through a lot of my projects, I feel as if I basically remained the same person. But there have been periods of transition. After I left Greenland, I was challenged to work in a new way – I was no longer photographing my girlfriend or people I lived with, but strangers I was meeting on the street. This felt strange at first and took a long time to adjust to, but mostly, as I’ve said, I continued chasing the same thing in all my subsequent work – being in love or finding love in others has been my way of survival and of finding meaning in existence.

J.J.: Did other photographers influence you?

J.A.S.: Yes; for starters, my mother and grandfather were both professional photographers as well. My studio is now in my grandfather’s old farmhouse in the Danish countryside, and we’ve found thousands of his negatives in the attic here; in a way, I’m continuing to live out his vision of using this place as a space for creating photography. We had recently converted his old horse stable into a darkroom.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: Back in the past, you said: “It is when pictures are unconsidered and irrational that they come to life; that they evolve from showing to being.” Would you say you are not trying to tell a story but to “take pieces” of life, focusing more attention on the visual result?

J.A.S.: I would say it’s true that I’m not trying to “tell a story” insofar as I don’t believe my pictures have a meaning or that they exist to take you from point A to point B through a narrative. My photographs exist to be felt, to convey a sense of shared emotion and the commonality at the core of each of our existence.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: Tell us about your intimacy with your figures.

Do you spend time with a person before the shooting in order to get into the right intimate atmosphere?

J.A.S.: It depends. With “Sabine,” the project was about her and her family and my life in Greenland. I lived there for two years, and initially, I didn’t take any photographs at all – I wanted to live the life of a hunter. Coming back home with a seal was much more important than coming back with a good photograph. Gradually I became more a part of the village, and then I started photographing again when it felt innocent and natural.

In Guatemala, I lived with the Gomez-Brito family in the mountains for two months – we worked together, ate together, and slept together under one roof, and I photographed throughout the experience.

My subsequent work in Tokyo or Bangkok became much more about sharing a short moment with someone – finding intimacy with a stranger in a matter of minutes or even seconds. In these situations, it becomes about making yourself vulnerable, opening yourself, and showing someone that you care about them and are interested in them in a real way.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: Tell us about your most important assignments or projects for Magnum or Leica.

J.A.S.: The project ‘Arrivals and Departures’ is a photographic investigation and interpretation of the historical railway from Moscow to Beijing. It is, in many ways, a project with multiple layers. It is a travel through time as we cross the post-communist superpowers mile by mile and gradually move closer to something that was historically the epitome of distant and exotic.

On this journey, the romantic imagination is confronted with the harsh reality. But the journey through Russia, Mongolia, and China is not only a travel through time and space; the pictures are just as much a journey within ourselves – an investigation of the emotional states that control us, inspire us and keep us moving.

It is challenging to define. But, the purpose of the images is not to define, but instead, to only suggest – to lure the viewer and inspire them to use the image as a mirror of their own inner life. It means everything that we can identify with the pictures.

They are a consistent investigation of our close relation to the world, and the camera is the instrument with which I try to create order, understand my surroundings, and position myself in time.

When I started my journey on the railway, I was most curious to see if my view of the world and on my surroundings would be any different if the movement took place as a slow-paced, long, continuous journey, where every house, tree, and village along the rail was passed. Would this “slowness” of the train create an even closer toe between the places and the people I met? In a time where everything moves faster and faster, the slow image seems to link even closer to the human need of being seen.

The journey on the railway is filled with meetings, landscapes, objects, and emotions – both discovered and left behind. The young Russian couples in love, the Mongolian children on the playground, and the rhythmic pulse of the Chinese capital transformed into a continuous stream of images.

The project Arrivals and Departures is an abstract visualization of the moments when we meet and separate when we see things for the first or the last time when we fall in love or leave behind. Told with the Trans-Siberian railway as the red thread that ties Europe and Asia together, faces with places and the viewers’ own reality with the emotions that the pictures provoke.

It was on my first travel of Arrivals and Departures that I got interested in the Geography North of Lake Baikal. I remember passing the lake on the Trans-Siberian, not being able to get off because of the already planned route we had made to be able to deliver the project on time.

The project had started as a collaboration with Leica Camera to launch their new pure black and white digital camera, and 50 of my best images were to be shown at a huge launch in Berlin. I still remember the last email from one of the Leica bosses just before departure: “Can you deliver?” it said and nothing else. “Yes,” I replied. It was my first time using a Leica camera and my first time shooting digital. They must have trusted me somehow because everything – the launch of the camera in Berlin one month later depended on the strength of my images.

After everything was over and I settled back in Copenhagen, the sight of Lake Baikal never left my mind, and from that moment, I knew that I was going to return. I started researching the North-Eastern part of Siberia – or rather Yakutia.

I was curious about this enormous underpopulated area of more than three million m2 – more than 12 times the size of the United Kingdom. I had never heard about Yakutia – I read about the coldest inhabited city in the world, Yakutsk, and of the village of Oymyakon, with temperatures down to -65 during the 6-month-long winter. I wondered how people could live there.

I read about the horse breeders in the south and another native population, the Evens – being reindeer breeders in the North,

and of their struggle to maintain their ancient culture. Their land had been occupied by the Russians when they started finding gold in the region in the 1880s and 1890s. These mines were developed extensively during industrialization under Stalin and accompanied the rapid growth of forced labor camps. And this is how the Road of Bones was built by hundreds of thousands of Stalin’s prisoners – some criminals and other political opponents of communism, earning it its name, “Road of Bones”, derived from the thousands of prisoners who died constructing the road and are buried in its foundations.

My pictures focus on the lives of the resilient people who remain, the gruesome history of the place, the nomadic way of life that came before, the harshness and beauty of the landscape – and the contrast of it all.

In 2016-2017, I went to Yakutia from January to March, with temperatures as low as minus 60 degrees celsius. Spending half of the Winter in Yakutia, my aim was to document life as it is lived every day on the border between civilization and the wild, unforgiving nature. Instead of leaving for Siberia with a tight schedule and a route planned out in advance, I allowed myself time to explore the region, to search for opportunities, to get involved, and to connect with the people I met along the way. Balancing the different layers of the project, I traveled to far-off mountain villages, to abandoned Gulag camps, and to the infamous coal-mining ghost town Kadykchan, where we camped in our tent in minus 30 degrees.

We then ventured North, deep into the Taiga to visit bear hunters and reindeer herders in the North of Yakutia.

In stark contrast to history and the “Road of Bones” itself, my pictures show the life and the love that exist here despite everything – without losing sight of the dark past that is, paradoxically, the reason for living in this remote region in the first place.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: Your Black and White is very extreme. No half-tones of greyscale. Is there an intentional psychological reason for that?

J.A.S.: There is no “intentional” planned out the logic behind the aesthetic – their look and feel come from some intuitive sense of my identity and my attempt to find a visual expression.

J.J.: You have exhibited and received awards in various countries. Have you ever encountered a situation in which your work could not be displayed or promoted in a particular country due to the content of your photographs?

J.A.S.: I had been censored twice by art institutions – in America and Russia… Never in China…It was a huge fight, and we were close to canceling in both cases – but in the end, we made a compromise.

J.J.: Photographers, and artists in general, often note a meaningful or memorable moment during their career. What was yours? Is there any story you’ve worked on that is particularly close to your heart?

J.A.S.: The moment when I stopped taking pictures to be a great photographer and started embracing life and love that was just in front of me. The moment I started taking part instead of watching.

Sabine has put on lipstick, high heels, and a polka-dot dress. It’s the christening of her sister’s first baby. “Peqqeraava? Am I beautiful?” Sabine asks. She lifts her skirt up, revealing her star panties and a pair of laddered tights. “Lorunaraalid. You’re wonderful,” I reply, grab hold of her and start to dance. I’ve often watched Sabine dance in the village hall without wanting to join in. But now that we’re alone in her uncle’s house, I surrender to both dancing and Sabine. We dance across tables, chairs,

and mattresses — Wilder and wilder. Through the open window, we can hear the church bells chime, but Sabine insists: “Aamma, aamma, qilinnermud ilinniardiiatsiikkid. More, more. Let me teach you how to dance!”

My experience of creating “Sabine” has remained foundational in this sense, and I do believe the first story is often – maybe always – the best. Sure, you can deepen and refine your work in some respects, but it is impossible to replicate the honesty and impulse of the first project.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: On your website, there is a strong presence of your prints, books, booklets, posters, e.t.c. Is selling your photographs a significant part of gaining an income? What percentage of your income does work from personal projects make in comparison to assignments?

J.A.S.: Today, 100% of my income comes from personal projects. The last assignment I did was in 2017, making portraits in Siberia with a Huawei phone – a collaboration between Huawei, Leica, and Saatchi Gallery. Before that, it was Arrivals and Departures in 2012 with Magnum and Leica. Now all of my income is from books and print sales.

J.J.: Does the majority of your customers find your photographs via your website, a publication, or through exhibitions? Does social media play an important role in exposure for you – and to what extent?

J.A.S.: I can connect with a large fanbase directly through my Instagram and F.B., and I also sell and ship my own books and posters to people through my website. I do regular exhibitions with galleries and museums, and on rare occasions, I teach workshops like a recent one in Milan – all of these things have helped me broaden my audience and connect with new people. I feel very lucky to have been able to forge my own life – something sustainable that’s away from the industry and allows me to choose, day-to-day, what projects I’ll work on and share with people.

Copyrights to Jacob Aue Sobol © All rights reserved.

J.J.: I believe there are different markets for different styles of photography. What are the main nationalities of those who order your prints?

J.A.S.: Thanks to Squarespace, I have some very nice statistics about this. If you notice, the orders from Poland and Greece are only 1%… though I know I have many followers in these countries. But maybe they don’t have the money to buy my books. I want to make a gift for them…

Here are the top-selling countries:

USA 16 %, France 14 %, UK 10 %, Germany 10 %, Italy 6%, Holland 6%, Denmark 5%, Spain 3%, Taiwan 2%, Australia 2%, Singapore 2%, Norway 2%, Switzerland 2%, Austria 2%, Canada 2%, Belgium 1%, Poland 1%, Brazil 1% Slovakia 1%, Sweden 1%, Japan 1%, Luxembourg 1%, Portugal 1% Greece 1% Latvia 1%, India 1% … The rest are under 1%. We have sent orders to more than 60 countries.

I love the business part of being an artist. And I am better at selling than most galleries. We are close to being 100% in-house production at my studio.

J.J.: What is your typical workflow for when you work on a project? For example, the time spent in a particular location, the approach, your camera gear, editing, etc.

J.A.S.: I go long periods of time without photographing. At present, it’s been three years – that was the last time I was in Siberia working on my “Road of Bones” project.

It’s very important for me to feel hungry in order to work on a project. There’s nothing I consciously do to bring this about; sometimes, it just means taking part in life as much as you can and waiting until you feel the need to say something.

When I am working on a project, I work very intensely, often taking 1000 images a day. I might take hundreds of images on a single block of a street.

I photograph everything I see that I’m connected to, blocking out my thoughts and trying to remain completely open, avoiding any preconceived notions about people or places. Outside of my work on the street, I also do very intensive portrait sessions with people in their homes, taking hundreds of photographs of them in their most intimate space.

A lot of photographers shoot during the summer months and edit during the winter, but I prefer the opposite. Right now, however, I am in a period of editing my “12 Months of Winter” series, which means I’m going through lots of these folders from when I was working on a project and taking a thousand photographs, making a selection with my editor, Sun Hee, creating work prints with my interns, and then constructing book dummies from that.

J.J.: You use film cameras for most of your projects. Do you enjoy using digital? And how often do you use digital?

J.A.S.: I began using digital when Leica contacted me to create the initial “Arrivals and Departures” series in 2012. Basically, though, I think it’s important for people to use whatever they’re comfortable with. If you look at my images before and after I switched to digital, it would be very difficult to tell the difference. I do have a very particular tonality in my images, but that’s possible to achieve with either digital or film.

J.J.: In Denmark, do you mostly work on your own, or do you have a team under your care that takes care of social media platforms, creating the items for sale, etc.?

J.A.S.: I’ve worked with interns consistently for around a decade now, and I run the studio with their help. Our connection goes beyond just a working “studio” relationship, though. They bring a lot of new energy and ideas, and I try my best to help them as well and involve them in my life in a real way.

Since 2018 I’ve been building the Brothas Centre for Fishing and Photography in the Danish countryside, and young people have come here from all over the world to help build this place – Texas, Norway, Argentina, Canada, Ireland, Italy. It’s about creating a space where we can explore ideas of connectedness and sustainable living and bring together new photo projects as well, and it has been very intense at times – this all goes back into the photography, I think.

J.J.: It has been 20 years since you started practicing photography. What are your thoughts on the evolution of photography during this period of time?

J.A.S.: I don’t have any thoughts on the evolution of photography.

J.J.: Do you have a project in mind that you would like to take on in the future?

J.A.S.: Right now, I’m focused on going through my archive, which consists of hundreds of thousands of images from all over the world. I’m finishing my “12 Months of Winter” series, which incorporates a lot of unseen work from Denmark, America, Mongolia, and many other places. I also have plans for fuller books based on my work in Siberia and along the Trans-Siberian railroad. I also have unfinished projects like my work in America that I may return to in the future.

Last year I got married, and we had a wonderful daughter – Carmen. All of my love is there now… We will see what is left for photography or if the two will come together, as often happened to me before.

J.J.: What advice do you have for aspiring fine art photographers, starting in the field?

J.A.S.: Stay real = Be yourself = BE HONEST.