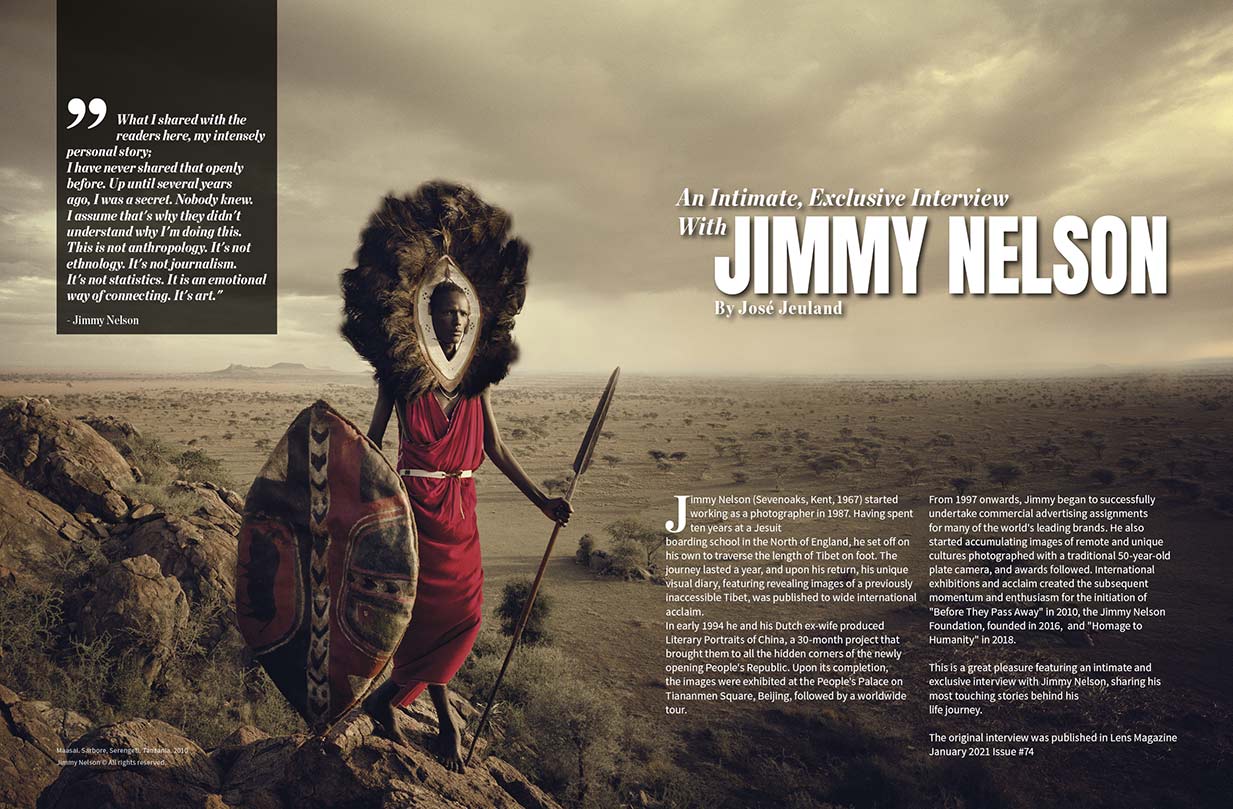

“What I shared with the readers here, my intensely personal story; I have never shared that openly before. Up until several years ago, I was a secret. Nobody knew. I assume that’s why they didn’t understand why I’m doing this. This is not anthropology. It’s not ethnology. It’s not journalism.

It’s not statistics. It is an emotional way of connecting. It’s art.” – Jimmy Nelson

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

WITH JIMMY NELSON

BY JOSÉ JEULAND

The original interview was published in Lens Magazine January 2021 Issue #74

” Dare to go on a different journey— a journey of self-fulfillment,

self-observation, and self-connection. Use your camera rather than looking for external gratification.”

– Jimmy Nelson

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: Thank you for this interview, Jimmy. It’s a pleasure to have you here; we have so many things to discuss. Can you tell us a little bit about your background? How did your photography journey start?

Jimmy Nelson: Yes, which means I’ve got to take you back a long time ago. I’m 52 years old. I first started traveling in the developing world when I was a baby. My father was a geologist. He collected stones, worked for an oil company, and every year we moved to a different destination, mostly in South America. For the first seven years of my life, I lived a very free, metaphorically naked existence. I felt a little bit like Mowgli from Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book. I lived in many different countries and cultures. But before the age of seven, my parents sent me to the U.K. to an institution, a Catholic Jesuit boarding school, with 1000 children and 400 Catholic Jesuit priests. It was a bit like a seminary, more like a prison.

Back then, I would spend 10 months of the year living there and two months of the year visiting my parents, wherever they lived in the world at that time.

What happened when I arrived at the Catholic Jesuit boarding school was quite confrontational.

First of all, I couldn’t read or write because I have been living in Bush (In different cultures), so they said: “You are stupid.” So that was the first label. The second label was that I have only colored friends, but I lived in Africa, so they were all colored.

So they said, “all your friends are black.”

I’d never understood the difference between their color of skin. Cause I was a child. So I’m stupid, and I have the wrong friends. Then, because they were traditional Catholic priests and we were lots of little children wearing shorts, four of the 400 priests were very bad, and they sexually horribly abused a number of us. So you come from extreme trust of the world to extreme abuse. In that process, I disconnected from any form of emotion. I stopped feeling anything because it was quite severe.

I spent my childhood living in this bipolar existence of looking at my body, which I hated because of the abuse.

As I reached the age of 16, entering puberty, while I was visiting my parents in West Africa, I had terrible malaria.

I went back to the institution, and I was given medicine. And because of the combination of malaria and stress,

my hair fell out in one night. So one morning, I looked in the mirror, and I had no hair; I hated myself physically, even more.

At that point, I hated my existence. I was stupid, Then the ugliness that I felt inside came on the outside. Now at the age of 52, having no hair is fantastic. Trust me, I love it. But when you are a child, it was the worst thing in the world because of what I felt inside. This isolation, this nakedness, and vulnerability, this pain projected itself on the outside.

So when I finished school, when I was 17, I ran away to the one country where I thought I could find a connection with other human beings.

While I was a child in this boarding school, I used Tintin, the protagonist of the popular comic book series The Adventures of Tintin, written by the Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi. Tintin was my avatar. And I lived as Tintin, undercover, worrying that the priests wouldn’t come and get me.

So when the priest came and did these crazy things to us, I closed my eyes, and I lived as Tintin in my mind.

I remember Tintin went to Tibet, which fits a kid with no hair. So I thought, where in the world can I go and find human beings that may see me inside for who I am and not judge me for my appearance, my pain, my isolation? This was in 1984.

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: Were your parents not aware of this terrible abuse?

Jimmy Nelson: No. They were English, and they didn’t talk about things. They just close the curtains.

“Let’s have a cup of tea and talk about the weather. Oh, it’s a nice day today. Would you like another cup of

tea?” That’s mainly one of the reasons I came to live in Holland. I love the Dutch culture and approach. They communicate. They’re straightforward.

Going back now to 1984, Tibet was closed for 30 years by the Chinese. And by accident, I walked the whole length of Tibet, crying. But what was beautiful was that although I was vulnerable, I was so naked and within despair; the Tibetian people are incredibly kind. They’re obviously Buddhist, and even though they were living behind a wall, they saw me in my pain, and they picked me up.

They took me with them. They adopted me, they fed me, they talked to me, and maybe they loved me.

So for the first time in my life, at the age of 18, I began to start breathing again. There may be a place for me in this world.

I have taken an old Russian camera with me, “Zenit,” four rolls of Kodak color and a gold roll film with these. And at the end of staying with each family or each community, I took a few portraits, very dignified, stylized portraits, because I wanted to remember the people who had looked after me with the beauty that I felt for them.

I came back to the U.K. two years later, with only four film rolls at the age of 19, but I was still alive. My family asked me where I was. I said, “I’ve been to Tibet.” they said: “This is not possible; Tibet is closed.”

They asked: “How did you live there?”. Well, I just went there, because there were no limitations, I had nothing to lose. I had nothing to fear because everything had been taken away from me.

So you just follow your heart. And by following your heart, you open up a whole new door to an entirely new journey of connection. And you start to learn.Through my journeys, I discovered that if you arrive with people very vulnerable and you put your arms up and say, “I’m nothing”. I’m here to see you. I’m here to learn from you, I’m here to be inspired by you – you start to develop a very different way of connecting with human beings. You’ve learned that you have to work a lot harder to show your spirit, show your heart, integrity, show your passion, and show your true, genuine love for other human beings.

But what’s weird is, many years later, today, wherever I go, I can communicate without using language.

You’re using your spirits. You’re using your energy or using your body. You’re using your passion and your obsession.

You’re using your centricity. And as the years evolve, I begin to see the more that I invest in the subjects, the people that I meet, the more that it’s mirrored back on me. And in actual fact, if you look at politics in a therapeutic kind of way, I want to feel empowered. I want to feel worthy. I want to feel beautiful and feel loved. But first I have to give that to somebody else.

As the years go on, you invest more and more; that becomes your mission.

Now I use an 8×10 plate camera, and I go on these journeys where I only take 10 pictures, but it’s these 10 moments of connection. These 10 moments of investments I’ve learned. The more you invest, the more passion, the more access you are interested in, the more obsession, the more admiration, and the more admiration, the closer you come. And if you invest it all, they won’t let you go because they see you see them, they would like you to stay. And that’s what I’ve been looking for – a sense of belonging.

So that’s how it started. Today, I take pictures, but there was a lifelong journey of reconnecting to trust, love for the world, and the people in it. That’s how I felt when I was an early child.

Chari-Baguirmi region Chad. 2016

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: When you went to Tibet, how was your relationship with your parents?

Jimmy Nelson: It was brutal. I’d be living away from home. Since I was seven years old, my parents left me there. They meant well, but they didn’t understand what was happening. And I felt furious.

How dare you let this happen to me? And because they were English, they didn’t know what to do. They didn’t say anything. And I felt at the time, I now understand in hindsight that it was not their deliberate intent.

This happens to a lot of children. So you are alone, and you decide, well, I have to find a way to reinvent myself because, as I now feel, I don’t want to live.

So the camera is, for me, it is still a metaphor. It’s a way of connecting with other human beings, how I want to be connected with myself. So I’m obsessed with photography, but not with the camera; I’m looking for the foreplay, the journey to the moment you take the picture. So the photography diary from Tibet was published. Somebody said, “Here’s a little bit of money.”

When I was 20, I went to Afghanistan for a year at the end of the Russian occupation in 1988. And then for six years, I only did war photography, but I was not a war photographer. I was still in pain, and I felt more comfortable living in an environment where people hurt each other.

José Jeuland: Did you publish the images from Afghanistan?

Jimmy Nelson: Yes, of course, also from Yugoslavia, Salvador, and Nicaragua, Congo, but they were not good journalistic pictures. They were just me, disconnected from myself, having an excuse to be in an environment where people were hurting each other because it alleviated my pain.

When I was 24 years old, I got married to a Dutch lady. That’s why I’m here. She used to say: “If you carry on doing this, you will die.” She was right. Regarding our relationship – We didn’t really want each other in a romantic sense. We are not together anymore, but we are still good friends, and we wanted to build a family and raise children. As we got married and started our own family, I switched to commercial photography.

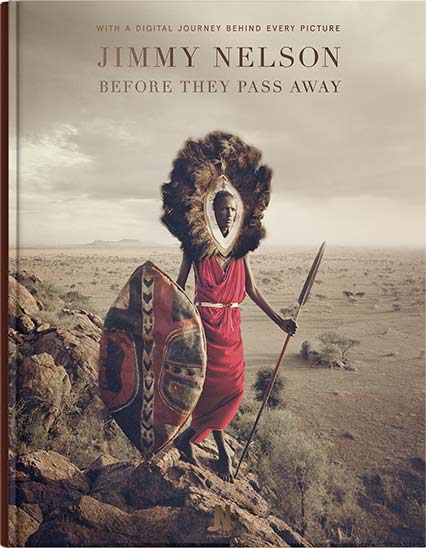

José Jeuland: So when was the point where the “Before They Pass Away” project started?

Jimmy Nelson: I think the project started as I was a kid, but in my early twenties, I worked in commercials; still, my hobby was always indigenous cultures because this is where I felt connected. For 15 years, I did it as a hobby next to commercial work. And then, 10 years ago, when digital photography was taking off, my commercial career had died, like for many photographers.

I was in a very privileged position using analog film, doing car photography, lifestyle photography. It was a very lucrative business. But when everybody got a digital camera and a smartphone, commercial photography, to all intents and purposes, disappeared, or your day fee went down to ten percent of what you used to earn. My marriage was going through a challenging period. That was the point where I felt the pain in my life, a little bit like a child again. I decided that the only time I’m happy is when I invest time with indigenous cultures because I feel connected to them and love nature.

Ten years ago, I said goodbye; I’m going to go back and start this project.

Everybody laughed at me. They said it’s a waste of time. “Nobody wants to see pictures of tribes,” they said.

“Well, I don’t care what you want anymore. I know what I need. So I’m going to make it for me. I’m going to go on a journey for me, not for you,” I replied. The indigenous people are the ones that make me happy. They are kind to me, and this is where I feel most comfortable. These are the people of the most beautiful model. Also, I had not really completed the journey of dealing with what I’ve been through as a child.

I realized that when I was young, I was not truly healthily balanced yet. I decided I have to reinvest in me, and the best way to do that is to put myself at the feet of others, but others who do not want anything from me other than to be seen and respected.

José Jeuland: That’s a very courageous decision to make, and the project’s outcome was very and still unique in the art photography field.

Jimmy Nelson: And yet, it’s not about the photography itself. This may sound a little bit arrogant, but please forgive me. It’s not about quantity or the photography goal for itself. It’s about the quality of connection. With so many community people, I’m building a relationship. Sometimes I have to go three or four times before they are comfortable standing in front of the camera. It’s an ever-evolving wheel of interest of connection, of growth, of accumulation, of material.

It’s an unending wheel of discovery and curiosity.

José Jeuland: And how do you actually approach them as you arrive for the first time?

Jimmy Nelson: Many, many years ago, when I was a teenager, I had no debt. And I felt terrible. I was fascinated by how people looked at me, and people interacted with me because they were judging me. They were scared.

They were pushing, so I decided to create my own kind of street theater as an experiment.

I was in London at that time, and I dressed up as a punk.

I put on a big Mohican, earrings, and fake tattoos. And I sat on a wall where there were many tourists with cameras. Half the tourists would shoot me at a distance. These people wouldn’t look at me. They would laugh, and they would walk away. They made me feel very angry.

Other tourists would come and sit next to me on the wall. They would look at me. They would ask my name and maybe offer a cigarette. They would compliment me and ask me about my life. And then at the end of the conversation, they would say, “Please, would it be possible if I take a picture of you?”.

The people who invested their time in me are the ones I would give the rest of my day to. So this was a vital lesson for life in general and for my later on projects.

You first have to give. So when I go to a community around the world, I will sometimes go for one or two months, not take a single picture, come back and go back the next year or another month. And only when they’re ready and comfortable, with the understanding of what I’m doing, then it becomes this dignified documentation.

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: Practically speaking, without a mutual language to communicate with, how do you come to an understanding?

Jimmy Nelson: It arrives naturally as you arrive. You become very small. You do not arrive with an entourage. You do not arrive with assistance. You do not come with helicopters or in Jeeps with 800-millimeter lenses. You arrive very small, very vulnerable, very afraid. And you wait and wait for making contact with one person by touching, looking, by the physicality and emotion.

Most often, it’s the chief or an elder or somebody wise in the community that arrives. Then you explain, I’m here to see. Then you’re looking, then you get out the camera, so it’s like a stroking process. And eventually, you begin, they begin to feel seen and acknowledged.

Then I go into the village and get the rest of the community. So all the portraits are made with a daylight studio, but a human studio. If you need 10 assistants, I use the villagers as assistance. So I’m running around, altering the light from the reflectors, obviously, then it’s indirect light. It can be a very long shutter speed.

The camera is on a tripod. So it’s a very, very, slow process of seduction, of flirtation, of compliments. You end up spending sometimes one, two, or three weeks only taking portraits, but it’s from a low perspective looking up, and each one is aligned.

It’s not something you shoot at. It’s something you build up a relationship with. You have to submit to the passage of time. If you go with an agenda and say, “Here’s my schedule, here’s my budget, here’s my deadline, here’s my date,” – forget about it. That’s how we live in the developed world, and this is why we have problems. If you submit to the process and to the journey, you don’t know where it will take you. You have no expectations. You need to let the journey take you. What will happen when I get there? It doesn’t matter because the journey is the process. Then you become part of it. And it becomes much more of an organic intrinsic spiritual journey.

Jimmy Nelson © All rights reserved.

José Jeuland: So as you visit them, do you sleep in the village? Spending all of your time with the community?

Jimmy Nelson: Yes, I’m always with them. So 24 hours together brings out the process.

José Jeuland: Let’s discuss the criticism you received about the project “Before They Pass Away.” Such a harsh criticism, claiming it’s actually not featuring the indigenous cultures in the right light.

You found yourself defending the project in an interview on the BBC, among many other newspapers and magazines. What I’m interested in is to talk about this experience from your personal point of view because you were putting your heart and soul into this project; it was a way of reaching recovery, an emotional process. As a result, you receive all this criticism. How did it make you feel?

Jimmy Nelson: That’s a good question. There are three or four answers. First of all, the criticism was unexpected. Yes, of course, it’s happened in the beginning. In 2014. 95% was positive. 5% was negative, but it was a very harsh negative.

I was very upset because they had no idea what they were saying, but it was still criticism. It is still online.

The results were two or three things. One, it makes you fight. It makes you dig deeper. If you are sincere in what you’re communicating and why you’re communicating, you will go to a deeper and more profound level.

If you have created something that is a fabrication, you give up in the fighting. If it wasn’t for the criticism, the project would not be where it is today.

Weirdly because the criticism gave it plenty of media attention, much more than any other project of mine.

And through that media attention, it evolved. Strangely, looking back, without the criticism, I wouldn’t be here today. It makes you grow. It makes you question why you’re doing what you’re doing. I have never shared my personal story that openly before. Up until several years ago, I was a secret. Nobody knew. I assume that’s why they didn’t understand why I’m doing this. This is not anthropology. It’s not ethnology. It’s not journalism. It’s not statistics. It is an emotional way of connecting. It’s art. This is how I feel when I’m in these environments, this is what I see and want to share. I started to question why people are upset with this project. I began to analyze this. The pictures are beautiful. They are meant to be beautiful. They’re indulged. They’re romantic.

Some of the photographs take weeks to take, but they’re all real. They’re not photoshopped. They’re not fabricated.

This is precisely as it looks when you’re there. The photos are not what you used to see in National Geographic, crawling through the mud on the floor because they’re poor and naked.

If I come to you and I say that I’m going to photograph you in two ways. One will be on the cover of Elle magazine, at the studio with makeup, in a stylish way; the second is at home, without makeup, and after a long night of over-drinking, both of the images will show the truth. Both are correct. In the developed world, we don’t give indigenous people the time and the dignity to prepare for a shoot. I turned it upside down. This project is the confrontation. We thought we were the rich ones.

We thought we were the ones in control. We’ve thought we were the ones with everything. But they are the ones

who look so healthy, So strong. So dignified. And it hurts. I think that’s where the criticism comes from.

As the project has grown, many of the journalists who confronted me at the beginning have actually come back and say, “We now have a better understanding of what you’re doing.

It’s still not journalism, but we understand the spirits as well. We understand the intention, and it is right to dignify these people”.

“It all goes right back to the beginning. When you have experienced such pain and darkness, you choose to live as a little child; you can only wake up in the morning and be positive and see the lights. At 52 years old, I still can’t forget it. I begin the day, all guns blazing because I’m going to celebrate the day, and being here, it’s worth it.

And that’s how I live. “ – Jimmy Nelson

José Jeuland: The was also about the title saying “passing away.” Are they really passing away?

Jimmy Nelson: The title was a little bit facetious, but it did create this discussion.

Something is passing away; The value and the wealth of their culture, that understanding of humanity. They are in transition.

Half of the world has a smartphone. That means 50% of communities. Obviously, some now have a Chinese version of a phone of G, 2G, 3g, even 4g. They see pictures from the developed world. It reflects on themselves. They are on the tipping point of abandoning their culture, throwing away the heritage, and putting on a t-shirt.

My project with the foundation is visiting and saying, “Oh no, what you have is extremely powerful, extremely beautiful and valuable, aesthetically, culturally and in your knowledge of who you are and how you exist with one another and the natural world, you have to hold onto it.”

So if we don’t act, if we don’t communicate, if we don’t share, if we don’t make these speeches and talk about it, they will abandon their heritage and follow us into the developed future.

My argument is, if you look where the world has overdeveloped, it’s now eating itself alive in the United States. No human being can say that culture is a success. 50% of them have no connection with their physicality.

They’re overweight. They’ve three times more guns than other human beings. Any nation in the world that prioritizes the destruction of human beings over-investing in its natural environment leads to destruction.

The U.S. had one of the richest cultures on the planet, the native American Indians, but they were looked upon as backward and primitive, as impoverished naked with feathers and horses, but their whole existence was animism. Look at how they are living now. Look at what’s about to happen tomorrow. The whole world is crying with me. I’m melodramatic for the sake

of humanity.

I don’t consider myself a fine artist when I walk into a studio and create an already existing environment. I’m just the mediator in between. So I take pictures. I make books, sell photos, but 20 to 30% of what we earn, we put back into the foundation to keep the circle of reciprocity. What you’ve given me, I want to give you back in return.