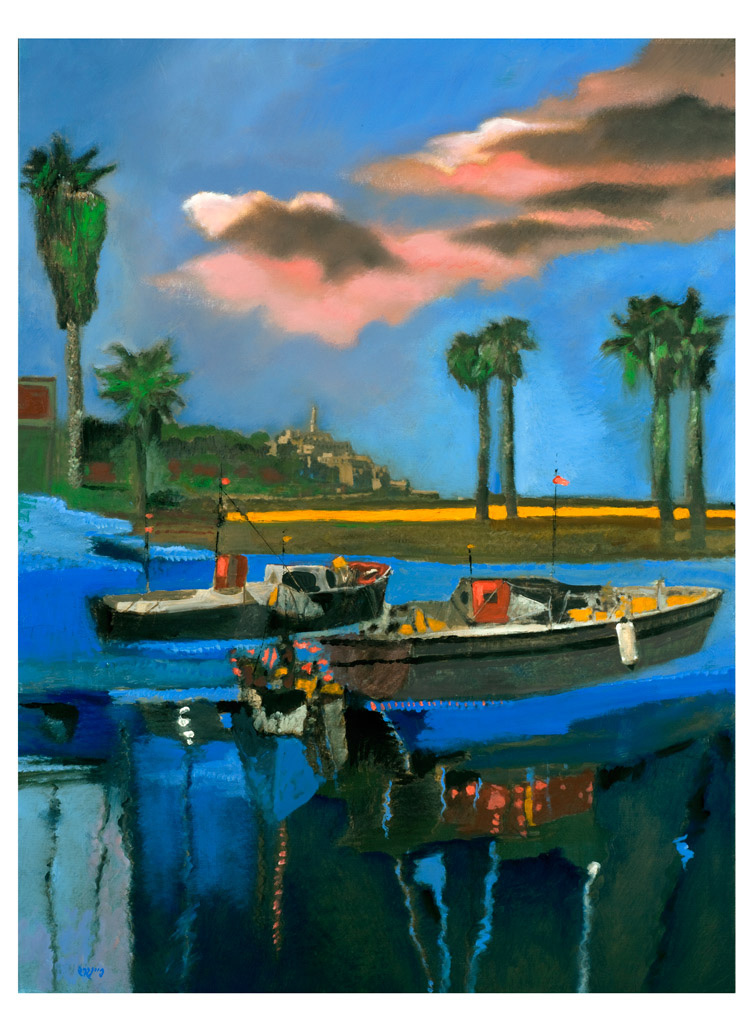

ODED FEINGERSH

Israeli Landscapes

THE TERRITORIAL WAR

The land of Israel: a land of flowing with milk and honey of its wildflowers. A land of vipers and scorpions, of deep valleys and mountains that kiss the blue heavens. Where the rivers of the Garden of Eden flows all around, through and within -bringing water to the entire land. A land of colors and aromas, true believers and charlatans, righteous and wicked-land of thousand aspects, perfumed with rose water, spices and magical charms.

Man is cast in the form of his homeland. The landscape has been, and continues to be, the dominant motif in the work of israeli artist ever since the beginning of the last century. For generations of immigrants, who came to her from afar, the shape of the land took on ideological significance. The sought their roots, and emphasized their newfound bond to the promised land by painting dancers of Hora, the sandy beaches of Tel Aviv, olive trees in the Carmel and images of ancient agricultural life.

In the Galilee they sang of the earth and their departure from the mythical Jew of exile-

a dunam here, a dunam there – and created facts on the ground. The Hebrew farmer followed his oxen, and dug furrows into the soil of the Holy Land. Cutting his figure as a man of the exotic East, a biblical figure climbing out of ancient scrolls.

The Betzalel Academy of Art, established in 1906, was named after Betzalel, the son of Uri, son of Chur of the tribe of Judah. Betzalel built the Tabernacle of God, the Tent of Meeting, as the tribes of Israel wandered about the desert. During the early years of the Betzalel Academy, students painted landscapes in styles they inherited from ‘fin de siencle’ Europe. Romanticism, also known as Jugendstill, and Art Nouveau dominated the output of an entire generation of artists at Betzalel. Their style was richly imaginative, playful and piquant, and the Zionist artists employed varied local elements as Europeans enchanted by the exotic Middle East. Shepherds of the land of Israel exemplified the local color, their heads wrapped in kafias, their bodies cloaked in flowing wraps of black goat’s wool.

The artists were themselves pioneers, dividing their efforts between paintbrush and hoe. Their landscapes are marked by a touch of deliberate naivet, used at first to distance themselves from the styles of European cities that bore the weight and traditions of anti-semitic regimes. Rustic naivism measured an idealistic stance against urban sophistication. Landscape painting became a natural part of the local environment – without any connection to Jewish tradition or to biblical illustration.

Modernism was heralded by a new freedom in wielding the paintbrush, the use of a vivid array of colors- “asif the grey clouds of Europe had vanished, and were gone”, as mentioned above, already in 1926. Jerusalem and the Galilee had become favorite

topics for artists, as the new city of Tel Aviv was still just beginning to blossom, comprised of a loose collection of scattered Jewish neighborhoods.

In the wake of the pogroms across Europe, and the rise of the Nazis to power, new waves of immigrants flowed into Israel, and an artistic tradition dominated by academicism and expressionism sprang up naturally around the Betzalel Academy in Jerusalem.

The output of the new generation of artists was characterized by woodcuts and monotone drawings, in which the role of color was secondary. From the exotic orientalism of idealized Hebraic styles the artists returned to the principles of the Jewish universalism. They explored a world of symbolism – ancient trees as expressions of solitude, sharp thorns to communicate the realities of daily life in Eretz

Israel, and ruined homes to represent the misery of their circumstances.

Against this backdrop, Tel Aviv, instead of Jerusalem, became the focal point for all of the new artistic spirit beginning to arrive from Paris. French impressionism, plays of light and shadow, and fleeting moments frozen in time. To begin with, they painted oil painting landscapes at sunrise or sunset, in homage to the European color palette, but these were later abandoned to lyrical abstraction and watercolor compositions better suited to expressing the wide scope of the new aesthetic.

Landscape painting also provided connections for new schools of art that came from Europe and America. Great fields of pure color, geometric shapes, new media, conceptual and minimalist art and color theory all came from the world of advertising.

The national condition, and the ongoing conflicts with Arab nationalism returned to the forefront, causing the landscape painting to bear direct relevance to current events. Accompanying the desire to integrate with the greater world and the Global Village, a clash of cultures began to rage within Israel, arising from the romantic idealization of the land at the beginning of the twentieth century, and extending to the territorial wars that marked the end of the century. Decades passed in between, yet still painting of stone cairns, olive trees, the sands of the coastal plain, and the curve of the hills of Judea retain their potency with regard to place and to current events, and remain as provocative as ever.

Oded Feingersh